Why No One Grows Up Anymore—And What’s to Blame

On the infantilising effect of modern culture, and the economic causes behind it

The Death of Adulthood

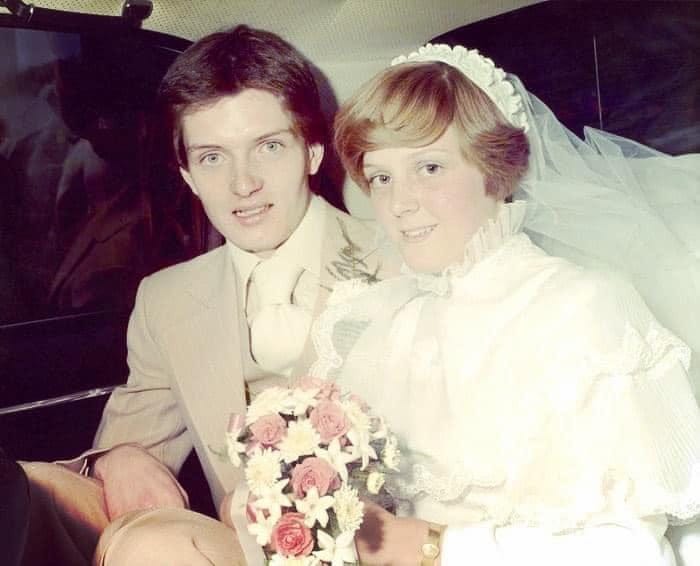

I once saw a photo of my uncle aged 27, holding his new-born third child.

“You were already looking pretty old there,” I tried to tease him. (In fairness, in the photo he was sporting a very respectable handlebar moustache. This wasn’t an affectation - he was a fisherman.)

“I had three kids to support, Mike,” he explained. “That tends to age you a bit.”

He was of course right. People did age younger then. They had to. We used to consider people adults at 18. Now, at 27 or even their early thirties, many are still on the runway, not yet cleared for takeoff. They have degrees, online portfolios, and therapy-speak by the yard, but no house, no mortgage, no marriage, no idea how to change a plug or deal with rejection without calling it trauma. It’s not their fault. You cannot become an adult in a society that gives you no material means to do so. But neither can you grow up if your cultural diet tells you that responsibility is oppression, and hurt feelings are medical emergencies.

There’s a reason people used to marry young. It wasn’t naivety. It was the simple fact that they could: there were jobs, houses, and social frameworks to support early independence. Council flats and houses existed. So did apprenticeships, industrial jobs, and predictable career ladders that weren’t built from unpaid internships and begging for freelance gigs on LinkedIn. You didn’t need to have read Foucault to move out of your parents’ house, you needed a YTS placement and a bit of luck and gumption.

Now? We have a generation of well-educated, culturally literate 25-year-olds who live at home, can’t afford rent, and explain their emotional pain using the same vocabulary they use to diagnose fascism. Heartbreak is “narcissistic abuse”. Confusion is “gaslighting”. Disappointment is “a trauma response”. In place of experience, they’ve been handed terminology, not tools for living.

This is not an attack on the young. It’s a lament for what we’ve taken from them: the chance to become adults by living like adults. Because without the scaffolding of work, housing, or long-term relationships, the only available identity is perpetual youth: a limbo of delayed consequence, endless potential, and simmering anxiety. And when that becomes unbearable, the fallback mode is victimhood. If you can’t win the game, declare it unfair. If life kicks you in the ass (as it does everyone), post a TikTok about your attachment style and call it healing.

Adulthood is not a feeling. It’s a state of being. It’s the ability to face reality without crumbling. And if we no longer encourage i,t then we shouldn’t be surprised when it disappears, or when entire generations mistake the common cruelties of life for violation of their entitlement.

And worst of all: they are not entirely wrong.

The Bank of Mum and Dad

The modern economy runs on venture capital, but for most under-40s, the only ready cash available is called Mum and Dad. Parental support has become the welfare state for the middle class, underwriting everything from studio flats to postgraduate degrees to delayed breakdowns in Bali. It's no longer embarrassing to rely on your parents into your thirties; it's sort of expected. You’re not a failed adult. You’re a “young creative” with a flexible domestic arrangement.

In another era, parental help was a favour. Now it's practically a prerequisite. According to data, more than half of first-time buyers under 35 in the UK receive financial assistance from family. The rest are largely locked out of the property market unless they work in depressed cities, marry into equity or win the postcode lottery. Home ownership has become a caste marker, a hereditary right. Inheritance has replaced aspiration. As financial rewards move ever more from labour to capital, the old get ever richer. According to CBS, people over 55 controlled about $74.5 trillion in wealth at the start of 2019 but by July 2023, that had jumped to $97.3 trillion - or more than 10 times the wealth held by people under 40. And where America leads, the rest of the world follows; and so the Bank of Mum and Dad flourishes.

This economic dependence has psychological consequences. Have you noticed how many actors, models, musicians and writers come from successful parents? Nepo babies like Romany Gilmour, Miley Cyrus, Jaden Smith, Liv Tyler – these little buggers are everywhere. Good luck trying to get into those industries. More mundanely, if you live in your childhood bedroom at 29, surviving on Deliveroo, freelance copywriting gigs and occasional parental top-ups, it's hard to imagine yourself as fully formed. You may know how to explain colonialism’s legacy in South Asia, but you don’t know how to register for council tax or what to do when the boiler dies.

But of course, this reliance isn’t benign. It comes with strings, both material and emotional. Your parents aren’t just lenders. They’re backseat life managers. They paid the deposit, so they get an opinion on your partner, your diet, your job. You are simultaneously infantilised and surveilled, given the tools of consumption but not the status of adulthood.

The old line was “if you’re under my roof, you live by my rules.” The new one is “If you’re on my payroll, you live by my rules but feel you shouldn’t have to.” That tension between economic dependency and moral autonomy is the defining contradiction of modern young adulthood. And it is producing not only delayed development, but a culture of profound anxiety, in which real adulthood feels not just unattainable, but unfairly withheld.

The Credential Trap

Since the 1960s or so, university education was sold as the golden ticket. Not just to employment, but to maturity, even to life itself. It was where you’d form your identity, meet people who would become lifelong friends, read big books, debate ideas, maybe even drink cheap lager and develop a sex life. The expansion of higher education was meant to democratise opportunity. Instead, it prolonged dependency. Degrees became the new basic qualification. Then came the master’s, the unpaid internship, the “junior role” at 28. In these kind of roles, you’re not an adult, you’re still circling the perimeter. University didn’t mark your exit from childhood but, rather, gave you a vocabulary to explain why you’re still in it.

And in this world, the prize is not wisdom, but credentials. You stack them up like protective charms: BA, MA, PhD, PGDip, MFA. Each one postpones the terror of real life by another year or two, and offers a new acronym to hide behind. But the more you accumulate, the more it hurts when you finally collide with reality. Because no degree teaches you what to do when the job you want doesn’t exist, or when love ends, or when the rent goes up but your freelance gig doesn’t.

So instead, the adult world is viewed with dread: as a series of coercive systems designed to crush your spirit. The workplace isn’t somewhere you might flourish but a site of exploitation. Family isn’t support but emotional entrapment. The idea of growing up becomes suspect. “Adulting” is a verb now, ironic, exhausted, already disavowed. You don’t become an adult. You do adulting, like you do laundry or community service.

And so education, once the road into the world, becomes a way of staying out of it. You become fluent in theory, and estranged from life.

Snooker player Willie Thorne, in 1986. He was 32.

The Psychologisation of Everything

When material adulthood is delayed - no house, no marriage, no kids, no job with a pension - what remains is interiority. If you can’t build a life, you analyse one. The external world is blocked, so the internal world becomes the main terrain of meaning. Which is why so many young people now narrate their lives as if composing a case file: every emotion labelled, every relationship autopsied, every wound typed up in clinical language.

Emotional vocabulary has exploded, but so has emotional fragility. The lexicon of mental health is now used to explain everything: breakups, awkward conversations, disappointment, boredom. Once you would have been heartbroken. Now you’ve “developed a trauma response.” Once you might have said he was a bit of a bastard. Now, he’s “a narcissist” who “gaslit me for months.”

This isn't to trivialise mental illness. On the contrary, it’s to point out how pathologised normal life has become. The therapy boom, TikTok psychologisers, the self-diagnosis culture, all reflect a generation trying to find order in their pain, but without the stabilising context of real adult experience. If your first real relationship ends badly at 27, and it’s your first because you lived in student housing until you were 25, then yes, it feels like a violation, because you’ve had so few formative collisions with the messy, necessary difficulty of love and adulthood.

And the digital world encourages this. Social media rewards self-narration, especially when it’s framed as suffering. “I left a toxic partner and found my healing era.” “I had to block my emotionally unavailable situationship.” These aren’t private reflections, they’re status updates dressed in clinical robes. Language that once belonged to therapists and doctors is now used by 24-year-olds who know how to project the right vibes.

This is the downside of emotional fluency without friction. If you’ve never had a bad boss, or been dumped, or failed at something real before your late twenties, it’s not surprising that your first serious hurt feels catastrophic. But instead of learning to metabolise difficulty, we’re told to medicalise it. To name it, own it, make it content.

This is not adulthood. It’s diagnostic autobiography.

The Collapse of Resilience

What we call fragility is often just inexperience with adversity. It’s not that this generation is weaker: it’s that they’ve been protected from failure for so long that when it finally arrives, it feels like an injustice. And because much of the scaffolding of traditional adulthood (work, marriage, responsibility, even plain old boredom) has been stripped away or postponed, there are fewer arenas in which to build the psychological muscle that used to be called resilience, and is now referred to, somewhat desperately, as “coping strategies.”

Resilience isn’t innate. It’s acquired through repetition, consequence, and friction. Through failure, embarrassment, loss that isn’t immediately re-narrated as abuse. Jesus, I have failed and failed again, at work and in love. These disappointments still sting but they didn’t ruin me. I learned early that life was unfair. I do not expect anything from anyone. Now, too many young people are encountering life’s essential unfairness for the first time well into their twenties or thirties, and often in environments that have trained them to treat discomfort as crisis.

Universities, for instance, now offer trigger warnings for novels, safe spaces for debate, and deadline extensions for emotional overwhelm. All of this is offered with good intentions, but the net effect is to recode ordinary struggle as exceptional suffering. If The Great Gatsby requires a trauma disclaimer because it contains “scenes of domestic conflict,” what happens when you encounter actual domestic conflict? If a breakup is an assault on your boundaries, what happens when you lose a parent, or a child, or a job? Can you imagine a fisherman refusing to go on a trip because he felt anxious? He had a wife and three kids to support. Never mind the risk of drowning. Suck it up, buddy.

This is what happens when when institutions prioritise safety over growth, and culture rewards victimhood over endurance: young adults whose first collisions with life feel not just painful, but illegitimate. Resilience isn’t about stoicism or silence. It’s about practising dealing with pain. And if you’ve spent your formative years in a world designed to shield you from consequence, from discomfort, then even a minor failure can feel like the end of something.

Cultural Infantilisation

If adulthood has been delayed structurally, then culture has rushed in to decorate the delay. People have an amazing knack of justifying the financially necessary. We now inhabit a society that not only postpones adulthood but aesthetically celebrates its postponement.

Once, adulthood was aspirational. It meant autonomy, mastery, a private life. Now, it’s almost subcultural, something only a few people still “do,” like birdwatching or Latin. The rest of us remain in lifestyle adolescence, forever curating our personalities via fandoms, Spotify playlists, and seasonal affective TikToks. The grown-up is a comic figure now: the uptight dad, the bitter mum, the taxpaying drone who doesn’t “get” self-care. We used to grow into culture, but now culture grows down to meet us. Film franchises about superheroes. Music is stuck in nostalgia, like 80s-style synthwave. Adult clothing is cut like toddlerwear, all oversized pastels and soft silhouettes. There’s nothing inherently wrong with any of this, but taken as a whole, it suggests something deeper: a discomfort with forward motion, a suspicion that growing up means becoming irrelevant, or complicit, or alone.

Social media has supercharged this, creating the illusion of endless adolescence: a permanent stage of self-curation, mood updates, and peer feedback. Self-expression, in this economy, is also be self-marketing, and youth, with its flux and malleability, sells better than settledness ever could. There’s no aesthetic or financial payoff to becoming a tax-literate 34-year-old who reads Hardy and understands car insurance. And so the performance of youth stretches further and further into adulthood, even as the material foundations of adulthood retreat. You have 33-year-olds speaking in the language of 19-year-olds ("I’m just vibing") while planning their third “soft launch” breakup post. You have people who cannot make a serious life decision without running it past their online followers for consensus and emoji-based support.

This is not moral decline but existential drift. If culture no longer tells you what adulthood is, and the economy no longer allows you to achieve it, why wouldn’t you linger in the soft lighting of permanent becoming? Infantilisation isn’t about pacifiers and cartoons: it’s about a refusal to cross thresholds. And if you never cross, you never arrive at adulthood, at independence, or at reality.

Ian Curtis (the singer from Joy Division), getting married at age 19, in 1975. Deborah Curtis was 18.

The Disappearance of the Adult Ideal

Not so long ago, there was a clear vision of adulthood. It may have been rigid, repressive, and often suffocating, but it had structure. You left school, you found work, you got married, you raised children, you participated in the world. The milestones were economic, social, and moral. They weren’t always fair, and they weren’t always kind, but they gave you a story to step into. The future felt clearly plotted.

Now, that certainty barely exists in media, politics, even in private life. What does it mean to be an adult now? It doesn’t mean home ownership. It doesn’t mean marriage -most people delay it until they’re already settled. It doesn’t mean parenthood - too expensive, too unstable. It certainly doesn’t mean community or civic duty, which have been eroded into abstractions, or mocked because our culture sexualises everything and people are afraid to mentor. We are a culture of unmoored grown-ups, improvising adulthood without a script.

The closest we get to adult aspiration today is “being in control.” But it’s the control of the self, not the world: emotional regulation, setting boundaries, cancelling plans. Adulthood has become an interior practice, rather than an exterior structure. It’s something you feel your way into, rather than something you perform through concrete acts. But when the external markers are gone, so is the collective imagination. People used to envy the successful adult whereas now they envy the unbothered one. Stability has been replaced by serenity. Sacrifice has been replaced by self-care. We once longed for the house, the spouse, the salary; now we yearn to not be anxious.

The result is a generation trying to grow up inside a vacuum. Not only are the institutions gone, but so is the narrative. No wonder so many people turn to trauma discourse and endless introspection - they’re trying to build a framework for life out of feelings, because that’s all they’ve been handed. We haven’t just delayed adulthood: we have deleted the map. And we’re surprised when people can’t find their way.

Conclusion: Time to Grow Up (Again)

This isn’t a screed against the young. It’s a post-mortem for a kind of adulthood that no longer exists, and a plea for something to replace it. Because if we don’t want a generation locked in a permanent adolescence of anxiety, nostalgia, and self-diagnosis, we have to do more than roll our eyes at their TikToks. We have to rebuild the conditions that made adulthood possible.

That means homes you don’t have to inherit. Jobs with dignity, not just Slack channels. Apprenticeships that pay, not unpaid “experiences” that drift into your thirties. A welfare state that treats independence as a right, not a reward. And yes - a culture that celebrates maturity without mocking it, permits difficulty without demanding diagnosis, and encourages mentorship and cross-generational interaction without inferring some repugnant sexual motive.

We also need to let the young fail earlier and recover privately. Growing up means getting things wrong without having to brand it as trauma. It means breaking your own heart without a therapist’s vocabulary. It means building your inner life through practice, not content. Right now, we’ve created a system where no one gets to make mistakes without narrating them, and no one gets to grow without permission. Because at some point, growing up will happen anyway. Loss will come. Grief will find you. The world will not accommodate your boundaries. And if all you’ve been taught is how to name your feelings, not how to hold them, this will feel like the end of the world.

But it isn’t. It never is.

The tragedy is not that young people are fragile. The tragedy is that we have left them no other way to be. We infantilised them with good intentions, delayed their independence with structural cruelty, and then mocked them for not becoming stoics in a storm. So yes, maybe it’s time to grow up again, not with shame or sermons, but with the recognition that adulthood is not a burden, it’s a gift. It is the ability to absorb blows, love badly, fail with consequence, and keep going.

Life is heavy. Life is hard. It always has been. But as the Beatles said, it’s about carrying that weight.

Nice read Mike! I think at the root of this is untapped growth in wealth inequality and the squeezing out of the middle class - almost everything else is a symptom. Most worrying is that our parents generation will be the last to have wealth to pass on to their kids - our own kids are fucked unless the system radically changes.

Awesome read Mike. This feels like the cornerstone of a greater cultural analysis. Mentorship, community, and civic duty itself feel like something you could really dig into. Or how all of this is very American and white - immigrant families understand the structures of the adult and look on us with pity if not disgust at how we've abandoned these cultural touchstones.