The Death of the Decade

How Cultural Time Collapsed, Truth Fragmented, and the Past Refused to Die

I. Did the 2000s Ever End?

The other day, I was reading an interesting thread on the r/GenX subreddit asking “Anyone else feel like “decades” stopped being a thing after the 90s?” Here are some of the comments:

I cannot distinguish music from 2000 to 2025 at all, but I can easily pinpoint the differences between the 50s through 90s.

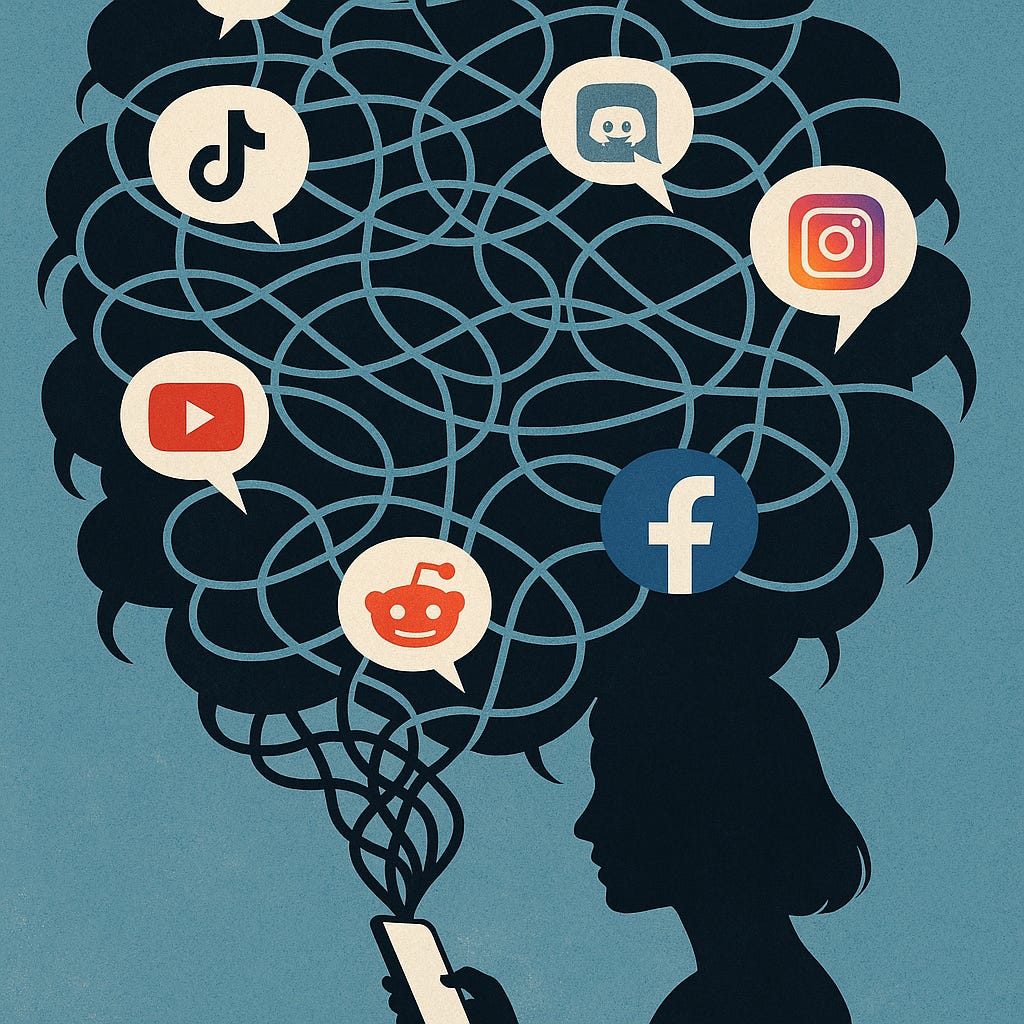

I think it’s because we stopped living in a shared reality thanks to the Internet, social media and smartphones. I’m not a fan of how things have turned out. Everything is dictated by custom algorithms for each and every one of us.

100%!! I met my husband in 2004. We have a photo on the fridge from when we first met. Other than the fact that we look older, it could have been taken today. I still have the shirt I am wearing in the photo and I still wear it. My parents were married in 1963 and photos taken of them in 1963 vs 1984 (21 years later) look like they were taken on a different planet

This is evidently a fairly common feeling. So let’s try to unpack what’s happening there and why.

In 1973, the poet Philip Larkin was asked about the decline of English poetry as seen in his Oxford collection, The Twentieth Century Book of English Verse. “There’s a feeling that the whole thing somehow disintegrates into a lot of nice amiable small poets,” the interviewer said. To which Larkin said: “That’s just what I think English poetry does.”

What Larkin was talking about was the way that poetry had ceased to be central to cultural life. Once, Shelley spoke of poets as “the unacknowledged legislators of the world”, Tennyson wrote sonnets on national foreign policy, and they mattered, and Yeats was so central to Irish cultural life that he was appointed a senator in 1922. But with rock n’ roll becoming culturally dominant by the 1960s, slower forms of culture like poetry ebbed away to niche positions.

And now you can see the same thing has happened to rock music. Central for three or four decades, it too has lost its cultural influence. Larkin in another interview said, “When I was growing up, we had Yeats, Eliot, Graves, Auden, Dylan Thomas, John Betjeman—could you pick a comparable team today?” For rock music one might say, “In the 1990s we had Nirvana, Radiohead, Garbage, Smashing Pumpkins, Hole, Oasis, Tool, Pearl Jam and Spiritualised; could you pick a comparable team today?” Okay, some might point out that there’s still great music being made. Bands like Animal Collective are terrific. Taylor Swift is as chart-topping as any pop artist ever was. But is rock music as a form still central to our culture as it once was? Of course not.

Times change. So what?

Well, think of it this way. It used to be that we could at least track the cultural shifts. The 1920s were jazzy, the ’30s were desperate, the ’60s rebellious, the ’80s indulgent, the ‘90s fun and peaceful. The decades had a distinct vibe. But trying to label the 2010s or 2020s is much harder. We’re halfway through the 2020s and all I can think of is “Covid” and “Trump” and “Ukraine”, but no overriding adjective, no coherent narrative. The sense of shared cultural time - of decades as story-shaped containers - seems to have decayed. It’s like that Red Letter Media video, where viewers are asked to describe Queen Amidala or Qui-Gon Jinn - and they can’t. The characters have no definition. They’re just there. The decades now feel the same, in high definition but somehow still weirdly unidentifiable.

The decades no longer feel like they have shape or consensus meaning. This isn’t accidental. It’s a symptom of the time and culture we live in. I’m not saying we’re living in a Matrix-style “Desert of the Real”. (Put away your tinfoil hat, yeah?) But I am saying the decades as we’ve known them are dead, and that death says something deeper about the breakdown of shared meaning itself. The death of the decade is a symptom of a broader Western epistemic breakdown: the collapse of shared standards, stable knowledge, and even shared meaning itself.

II. There Was A Time

The decade as a cultural identifier required two things: mass media and mass politics. Perhaps in the UK the first was the 1890s, with its Wildean decadence and imperial zenith. (Though I’ve read of Russian writers saying a character was typical of the 1840s so perhaps it was widespread elsewhere). As the railways opened the world and Western hegemony ruled, so the decades had coherent meanings. The 1920s was the jazz age in the UK as well as the US. The Great Depression was a worldwide phenomenon, and most countries were affected by the rise of fascism in the 1930s. Rock n’ roll and Abstract Expressionism cemented American cultural dominance in the 1950s. Hard power enables soft power which enables cultural coherence. You can’t have everyone drinking Coca-Cola without US Marines.

Cultural memory was shaped by political forces and the underlying structures of shared attention. When the majority of citizens read the same newspapers, watched the same TV channels (just four in the UK until 1997), voted in the same elections, and were conscripted into the same wars, a cultural consensus was possible. National cultures had a structure and meaning. You could track these rhythms not just in parliaments and protests but in pop charts, sport, and sitcoms. The decades had texture, atmosphere.

As someone who was born in 1979, I can instantly identify hundreds of examples of what made the 1980s and 1990s. The 1990s were about Friends, Oasis, Pulp Fiction, “You Get What You Give” by the New Radicals, Bill Clinton, the iMac, the Spice Girls, the PlayStation, Blockbuster Video, baggy jeans, and girls in colourful scrunchies. The 1980s? The Atari, Pac Man, Touchstone films, Raiders of the Lost Arc, Ghostbusters, Kylie Minogue, Live Aid, Rocky movies, the Commodore 64, Care Bears, the Walkman, “Take On Me” by A-Ha, Madonna, Mr. T, Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, Mikhail Gorbchev, Michael Jackson and the Thriller video.

The decades were so readable that numerous historians have written on them as identifiable wholes – Dominic Sandbrook on the 1960s, Alwyn Turner on the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, and political historian Peter Hennessy has portrayed the immediate post-war years. Saying something “was so sixties” or “totally eighties” is to invoke a huge cluster of associations (sporting, media, national, cultural), experienced collectively. But now, that structure of time - decades as meaning-containers - has gone.

III. Cultural Constipation

What’s wrong with modern culture? Digital culture means immediacy, which in many ways is great - I can videochat with my friends and relatives from across the world, and I can send messages which they see instantly. But it means there’s no gestation period for cultures to emerge. Everything is discovered and put online instantly. Whereas genuine pre-2000s cultural movements, whether the Beats or punk or rave or grunge or jungle music, took time (or had time) to evolve. Grunge for instance grew in the dank Petri dish of 1980s Seattle, with bands like The Melvins and Mudhoney lighting the way for later bands like Nirvana, Soundgarden and Pearl Jam to become huge. They had spaces, a scene, roots, a community. Same with punk: it didn’t come out of nowhere, but gestated around the Sex clothing shop owned by Malcolm McLaren and Vivien Westwood. Directly from there we get the Sex Pistols, The Clash, Bow Wow Wow, Chrissie Hynde and The Pretenders, Adam and the Ants, and Siouxsie and the Banshees, from whom came an entire new wave of bands.

But now the 24-hour media is voracious and no cultural trend has the chance to ferment and develop without distracting media attention. As soon as something emerges, it is packaged, posted, quoted, monetised, and spat out. There’s no underground anymore, no third spaces where ideas can mature before facing the world. Everything is online immediately; everything is now.

So the problem isn’t scarcity but saturation. We are drowning in content. There’s always a new documentary, a new viral video, a new album, a new Substack post. It’s impossible to keep up in the post-gatekeeper world. There’s just too much stuff. Everyone’s got their own favourites. But because of that, there’s no sense of progression or shared development. That’s why recent decades feel somehow empty despite being pumped full of content. It’s the junk food paradox: abundance without nourishment.

Cultural constipation, as I’ve written previously, is the inevitable result. Because if you don’t let culture ferment, it can’t replace what’s there already. Then nothing gets renewed, and we keep circling the same reference points, like 90s nostalgia, 80s fashion, and tedious intellectual property reboots from Aliens to Superman. We can’t move on because the system is stuck, and culture feels flattened, dead and timeless. Think about it – how would you categorise 2010s movies? Tough, isn’t it?

IV. The Annoying Philosophical Interlude

So we live in a time where nothing is forgotten, and nothing is remembered. Everything is accessible, but nothing means much. Culture once moved with a sense of direction, even if contested. Now it just blinks at us, asking for an update.

There are thinkers of late modernity who saw all of this coming. (They’re all French but bear with me). In The Postmodern Condition, Jean-François Lyotard declared the end of “grand narratives”: the collective stories we once told ourselves about progress, revolution, the triumph of reason, even the inevitability of capitalism. In their place, he argued, we are left with micro-narratives: individual, tribal, endlessly scrolling. You don’t belong to a nation or a movement anymore; you belong to a Discord, a subreddit, an X community. That’s why the 2020s still feel like the 2010s, which already felt like a remix of the 1990s. There is no great cultural shift, no decisive historical progress. Just updates.

Jacques Derrida, the father of deconstruction, pushed this further. There is no centre, he argued. No fixed anchor from which meaning flows. All meaning is relational, recursive, endlessly deferred. In cultural terms, this is deadly. Once the centre collapses - whether God, the nation, the novel, the avant-garde, or even the coherent adult subject - we have what he called “endless play”. But this means we no longer move through distinct epochs. There’s no socially agreed locus of meaning, just individual bubbles. Agreed meaning, and therefore agreed narratives, collapse. History comes to an end. Not as Fukuyama thought, with everyone agreeing, but through utter social disaggregation.

Jean Baudrillard, as ever, took it deeper. In Simulacra and Simulation (referenced in The Matrix), he describes a world in which we consume images without originals. A Coke ad is not selling Coke — it’s selling Cokeness, a vibe, an emotional response. (Why else would a cold drink insist on being so associated with Xmas?) Disneyland doesn’t just imitate fantasy but replaces reality with a better simulation. Nostalgia becomes sharper than lived experience. We don’t remember the 1980s (all those brown sofas and smoking indoors); rather, we remember TV shows presenting the 1980s. Our real histories are thus replaced by simulations of history: media-scaped narratives that belie the knotty realities of the period. I can see this online, in Gen Y complaints about how easy it was in the 1980s, as though that decade’s mass unemployment, AIDS, violent crime, high inflation, and rampant sexism and homophobia didn’t exist. They prefer to believe in the vibe of the 80s as presented through media, not the genuine lived experience of those who were there.

I think these ideas explain the feeling of contemporary culture: that everything is parody, reaction, revival, or repost, and that nothing adds to the narrative. You might say that Lyotard killed the story, Derrida dismantled the sequence, and Baudrillard buried the memory. The end of the decade is thus primarily epistemological. We are no longer agreeing on what’s true, or real, so we can no longer agree how to tell the bigger stories of our time. (Did you notice the Smithsonian museum trying to remove Trump from its impeachment section?)

V. The Future of Time

Let’s face it. The issue about the decades is fundamental to who we are. We no longer agree on what’s true because we no longer live inside shared systems of knowledge. Now we live in algorithmic isolation, each of us fed a customised hallucination of the world. The decade can’t come into focus, because there’s no common page – no center, as Derrida said, no grand narratives, as Lyotard wrote. Previous generations were shaped by common references: news channels, albums, political debates. Now most of us live in separate, ever-tightening feedback loops - TikTok, YouTube, Discord, Reddit, Instagram - each with its own logic, facts, and villains. The result? We don’t just disagree about policy - we disagree about what happened.

I don’t know how we fix that. Probably no one does. But maybe it starts by recognising that culture isn’t just expression but negotiation and collision. Negotiation requires a common table, and collision needs the courage to imagine outside ourselves. If we want the decades to mean something again, we need to get away from the screen and back to seeing each other as we really are – messy, human, and with far less dividing us than we have let ourselves believe.

Was already drowning in content and here comes another post, huff

Well-written!