The Constipation of Culture: Why Nothing New Gets Through and Nothing Old Goes Away

How late capitalism turned culture into content and content into sludge

1. The Extractive Turn

Is it just me or does something about modern pop culture feel somehow off? Not broken but stuck. A sense of stasis. There’s more content than ever before but less and less feels worth seeing or hearing. Those nostalgic Facebook posts showing what was playing on multiplexes in 1987 (Robocop, Platoon, Predator and Three Men and a Little Baby – sigh…) do suggest a serious problem with what’s happening now. It felt like we had good films and TV shows bursting out of our ears back then, both the conservative (in the UK, The Two Ronnies and Last of the Summer Wine) and the innovative (The Tube, Red Dwarf, and The Young Ones). There was space for both. Executives would take a chance. Cheers for example endured a season of poor ratings but its producers believed in it. The writing excellence was plain for all to see, as was the Sam/Diane, primitive/sophisticated, nature/culture dialectic from which so much comedy has been wrung. (Like, all 11 seasons of Frasier). Seinfeld was initially so unpromising that producers commissioned just four episodes for its first season. But it grew and improved. Simon and Shuster took a chance on publishing American Psycho when its initial publisher balked. Hellraiser was given a million dollars and writer Clive Barker allowed to direct it. (Imagine that now!) James Cameron was able to write and direct The Terminator after just one credit (for, um, Piranha 2).

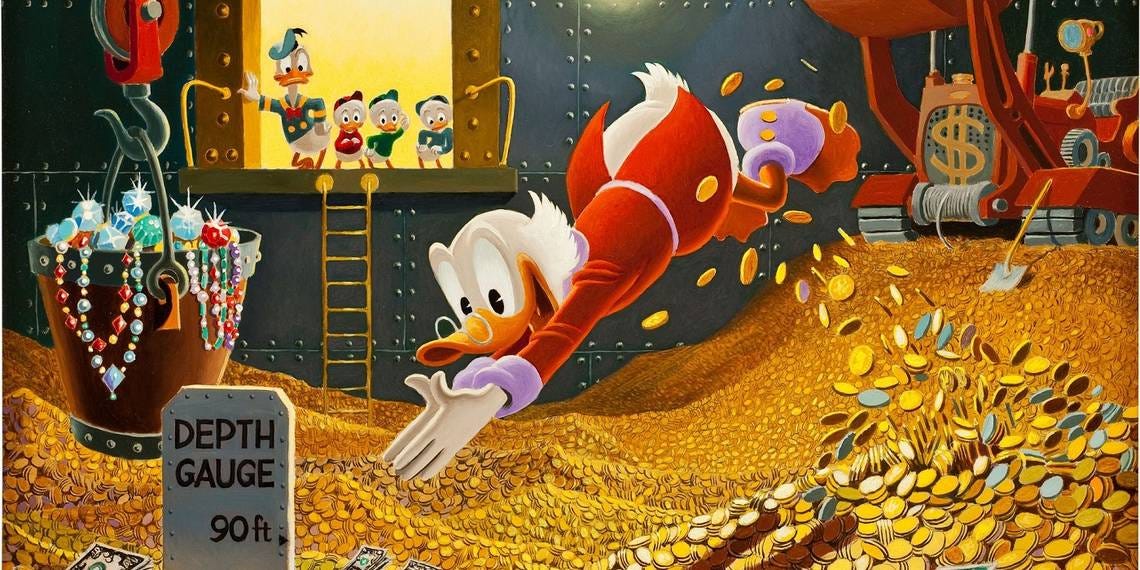

That spirit of innovation feels like it has been crushed in a tide of remakes, reboots and sequels. The mainstream cultural sector – the media conglomerates that control the films, TV and music that make popular culture – are decreasingly interested in producing their own intellectual property. They want it ready-made. They don’t create: they harvest. Like so many venture capitalists, they are more about extraction than generation. They sweat existing assets instead of enabling scriptwriters and directors. Why risk it? Why indeed, when there’s so much IP lying about with a near-guaranteed audience. The works of JRR Tolkien have become his own Moria, strip-mined for storylines, aesthetics, even mood, in the lust for wealth. Expect to see dramatisations of his letters or animated visions of his poems in the not-too-distant future. Gotta keep churning.

In publishing it’s probably even worse. Ghostwritten celebrity memoirs dominate the charts. Book deals go to influencers and personalities who “bring a platform.” Publishers say that these books are profitable and enable the real books they really want to publish, but bandwidth is limited. And good luck trying to get a book deal unless you’re already well-known. (I know this only too well. When I was trying to find a publisher for my Pink Floyd book, I constantly got the response: “Great book, love the writing, but you’ve no platform so no thank you.”) That’s how it works now: platform over prose, metrics over merit. (OK so I did get the book published, but my point still stands).

Music, meanwhile, feels like it’s in an even deeper rut. In the 1990s you still had new forms constantly emerging: rave, grunge, Britpop, nu metal, trance, drum and bass, jungle, shoegaze, new jack swing, big beat - each with distinct sounds, fanbases, and meanings. The 2000s were when this unravelled as the algorithm took over. Now, legacy acts charge hundreds, even thousands, of dollars a ticket while Spotify is home to infinite new bands nobody knows whom they pay fractions of pennies. People tell you there’s great music out there if you find it, but that’s the point: it’s lost because there’s no unifying point for rising artists. New music thus lacks cultural significance – everything legacy acts like Bruce Springsteen and Metallica have in such abundance. (Not that I’m above seeing Iron Maiden (twice), David Gilmour or Roger Waters. We all have our idols. But that shouldn’t mean acting like a musical Herod and killing the young).

“Ah!” I hear you say. “What about online culture? That moves fast. Internet companies come and go. Remember MySpace? And Bebo? And memes have the briefest of half-lives. That all changes constantly.” Fair point. But that’s social media, not the more complex products like films, TV, books and music. Online discourse has a vanishingly short shelf life because being online lets everyone onto something almost instantly. But what we used to call physical media takes longer to assimilate…

The shift hence is that cultural production is no longer about creation but memory management. Labels and studios don’t want to produce the next Robocop or Thriller. (Let’s not forget that when The Jacksons moved to CBS from Motown, this was seen as risky. Their musical credibility was low. But CBS president Walter Yetnikoff took a chance on them. They were nurtured.) But now it feels like media companies more often want to profit from the joys of the past. So we’re being fed pop culture history in a nightmarish feedback loop of creativity devouring its own corpse. Like BSE cows fed the remains of dead cattle, we’re consuming regurgitated culture and calling it a feast. This is not a healthy system. It is an extractive culture, and the sickness is spreading.

2. Platform Over Purpose

What is clear now is that media companies are interested in reach, not voice. Whatever moves the needle, baby. That’s where the market is. Of course, to some extent this was always true. Edmund White writes in City Boy: My Life in New York During the 1960s and 1970s of the “delirious professions”, “those careers that depend on self-assurance and the opinion of others rather than on certifiable skills. The delirious professions, I’d hazard, comprise literature, criticism, design, the visual arts, acting, advertising, [and] all of the media”. It was who you know (or “who you blow”, the more sardonic said).

But before the internet, those connections were pliable. You could hit the cocktail scene in New York or the publishing world in London and get to know people. That’s how Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe did it as hungry young things in New York. It’s how Clive James broke through in London after arriving from Australia. The scene was porous. You could bluff your way in, dazzle the right person, get your break. It was human.

But now buzz is quantifiable. It’s the numbers. How many Instagram followers you got? Are you big on X? Got paid subscribers on Substack? In other words: do you already have a name? Then we’ll sign you.

Take the YouTuber who makes videos about Japan. (I’'ll be nice and avoid naming him). He got a book deal. The book isn’t terrible, but it’s not great, either. It was shallow and trite (like still for example making penis jokes). Because someone who makes videos doesn’t necessarily have literary talent. But that wasn’t the point for the publisher. The platform was. They could pretty much bake in the sales by looking at subscriber numbers. Job done. Ain’t life sweet? Publishing books like that must be a doddle.

So it no longer matters if the work is good, or original, or necessary, or any of those artistic qualities we think ought to matter. What matters is if you come with built-in “reach” or “a platform” Have you got the metrics? And so editing has become algebra.

This cultural trend rewards safety and homoegeneity. It creates a market that’s allergic to rawness. So instead of emerging artists who experiment and stumble and get better, we get creators optimized for exposure, saying just enough to go viral but never enough to offend. We lose the workshop, the fuck-up, the breakthrough. But failure is where art lives. You can’t write Ulysses or The Waste Land or Nevermind without first writing the wrong things. The most popular podcaster in the UK started out writing porn for Forum, for god’s sake. (Though to be fair in between he did serve as the prime minister’s director of communications).

You need room to bomb. More importantly, you need room to be forgotten. Not invisibility (no artist likes that) but the ability to leave something behind and move on from it. The greatest enemy of an artist is often their own past. (Bono said that, but it’s a great quote).

3. Cultural Constipation

An online culture is one that does not forget. As people say about nude photos – once they’re out there, they’re out there forever. Even dead websites can be resurrected thanks to the magic of Archive.org. But this is building up some pretty nasty side-effects. One is cultural bloat. We have a culture that is unable to purge dead forms. Whether characters or styles (it seems like the 80s will never leave us thanks to synthwave and other related music sub-genres) or ideas, we seem stuck in a cultural moment that can’t let go of previous glories. Star Wars, The Beatles, Marvel Comics, christ even Hulk Hogan – they pop up again and again, not just relics of the past but constrictors of the future. Their continued prominence is less about enduring cultural value and more about brand recognition, nostalgia monetisation, and the easy comfort of the known.

It really just feels like every medium is clogged and congested with crap. In cinema, we get sequel after sequel: Jurassic World, Avatar, Ghostbusters, Scream, Indiana Jones, The Matrix, Toy Story. None of which seem willing to die, even when the stories have. Television is stuck in an endless feedback loop: Star Wars prequels (Andor, The Mandalorian, The Acolyte), Walking Dead side-series, a Frasier reboot, a Friends reunion. The Simpsons shambles on in its fourth decade like the cultural zombie it is. In books, we get the next Game of Thrones volume (maybe), the next Harry Potter prequel or reissue, another YA fantasy trilogy pitched as the next Hunger Games. Even Roald Dahl gets re-edited for “modern sensibilities” so we can keep selling him forever. In music, legacy acts dominate festivals, and dead stars from The Beatles to Abba to Prince and Tupac keep rising from the grave to releasing new material.

This is creative stasis being sold to us as abundance. Sure, there’s more content than ever, but almost none of it surprises. This is a culture, as EM Forster called it, “marked, not indeed with decay, but with the immobility that precedes it.” The unwillingness to face the new, to adapt, to innovate – these are warning signs from history. Just ask the Ming dynasty.

4. Innovation Requires Forgetting

What we underestimate about innovation is not its creativity but its destruction of old modes of thought and art. Every great artistic movement is its own Cultural Revolution, destroying the old to make way for the new. Sometimes you need to chop down a mighty oak to make space for new saplings.

Punk for example was perhaps the clearest reaction against “the dinosaurs”, fulminating against prog rock as much as creating a musical style-shift. Rock n’ roll too – what else is “Roll Over Beethoven” but an eviction notice? Move over, grandad, no more string quartets. Same with New Romantics – piss off, punks, we want colour and ambition and money. Same with Britpop – fuck off, grunge. It’s our turn. Rave culture did the same, its dance beats and collective euphoria making guitar music instantly irrelevant. How could you go back to Jesus Jones or INXS after that? Why would you?

Similarly, the Imagists and Dadaists of the 1920s dismantled Victorian sentimentality in poetry. They spoke to people in a new and modern language. TS Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” and particularly “The Waste Land” made every poem before them feel obsolete. Same for prose with Joyce’s Ulysses in 1922, and with Naked Lunch in 1959. They shocked the culture and destroyed the old. Nothing was ever quite the same again.

Culture needs these slaughterhouses, these clearing stations. It needs the right to destroy. But today it seems like we do the opposite. The instinct to raze has been replaced by a reverence that borders on necrophilia. We fetishize legacy. Paul McCartney is still touring in his 80s, as is Bob Dylan. David Gilmour and Bruce Springsteen are still drawing crowds while in their 70s. And then there’s Metallica, U2, and Madonna… This isn’t a problem in itself: the issue is that they’re treated as symbols of conscience and soul. Whereas most of them haven’t released a decent album in decades and some of their live shows are notoriously dreadful (looking at you, Zimmerman) or tacky cash-grabs (everyone else). So we need more disrespect. Like, Metallica’s last great album was in 1988 – nearly forty fucking years ago. Dylan’s voice has been knackered for decades. David Gilmour can’t write a good song by himself. Madonna looks ever more like a vampire sucking inspiration from the young. These are very mortal and fallible artists.

Our artistic veneration chokes the air so much that new artists are smothered. But to innovate, you must forget. There’s a very good reason why 1970s bands hated the 1960s. “No Elvis, Beatles, or the Rolling Stones,” said The Clash in “1977”.

And they were right.

Chop em down.

Chop em right the fuck down.

5. TV's Temporary Escape

“Aaah!” I hear another voice piping up. “What about TV? We have just been through a Golden Age of great television – The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, Mad Men, Game of Thrones, Succession. These shows were goddamn Shakespearean in breadth and depth. Explain that!”

I will. Put it like this: you know how car insurers and gyms throw the kitchen sink at you to get you to sign up? Then they bank on inertia to carry you through price hikes and added fees. Suddenly the deal doesn’t seem so sweet.

That’s how it was with TV. For about a decade (the late 2000s to the mid-2010s), we saw what television could be when writers were trusted. HBO set the bar with The Sopranos and The Wire, then Mad Men hit, then Breaking Bad - it was like the industry had hit multiple huge seams of gold. Writers had room to breathe, episodes were treated like modern plays, and audiences were seen as intelligent enough to follow ambiguity, character depth, and narrative breadth.

Netflix and Amazon jumped in, not out of love for the art but because prestige TV was how to get market share from cable. For a time, money was no object. But the moment passed, because the goal wasn’t to raise the cultural bar but to hook your subscription to streaming channels. Once they were big enough, once you were safely in their walled garden, the purse strings tightened and TV art gave way to "content strategy".

What followed is the era we’re in now: seasonal bloat, algorithm decisions, IP-driven spin-offs, shows judged on engagement metrics. I mean, look at the Frasier revamp. The original stands as one of the wittiest shows ever on TV. I utterly adore it. The revamp was a tired, idea-free landfill-sitcom that very obviously sucked. Paramount wanted to coast off the legacy of its former magnificence. Why spend loads of money on great writers? The fanbase was still there. But they weren’t after two seasons of mediocre dreck.

Perhaps even worse is the way that promising shows were axed if they didn’t take off instantly. The OA, 1899, High Fidelity – all were binned mid-stride. Maybe worst of all is where shows are killed for tax write-offs. Completed seasons like Batgirl or Minx Season 2 were shelved, unreleased, or erased to reduce short-term losses. Warner Bros. Discovery is the prime culprit here, but the practise is creeping everywhere. Culture is sweated and discarded, just so much product.

So no: the Golden Age of TV wasn’t a new dawn, where standards were raised, as happened with rock music in the 1960s or literature in the 1920s. It was just bait to get your money (and kill cable). Worse, it tells us that TV companies know how to make great television. They just usually choose not to.

6. The Cultural Barons

So why is all this happening?

It doesn’t take a genius (or a Marxist) to figure out that cultural trends are usually down to money. But it’s not just the financial numbers; it’s their structure. Corporate media concentration has followed the pattern of late capitalism: mergers, takeovers, acquisitions, all the diminution of consumer choice. Once there are three or four conglomerates, each is big enough to survive without being threatened by the others, and to swallow any up-and-comer that might be threatening. But with that lack of risk goes a complacency. So Disney can buy Star Wars from George Lucas and assume that it can pump out related films and TV shows regardless. So Amazon can buy the Tolkien TV rights for $250 million and produce uninspired dreck like The Rings of Power (currently sitting at 38% on the Rotten Tomatoes Popcornmeter from the public). Hey, these were hits films, so the logic is impeccable, right? Except they were expecting lightning in a bottle not just twice but through multiple seasons.

These conglomerates are the asset-strippers of culture, soullessly buying up all the big pop culture names in order to sweat them. Never mind what made them good in the first place – the creativity, the daring, the insight, the sense of the future being created. That’s gone. Now it’s about leverage, IP, and platform synergy.

The conglomerates' role in culture is hence no longer creative, but extractive: get assets, run them into the ground, then move on. But with such corporate power behind them, they are the perhaps more like new cultural barons - and we, the platform-serfs, are supposed to give them tributary eyeballs, buy the merch, and shut the fuck up.

7. The Generative Margins

But there is hope. There are places where there’s still humanity in our culture. Nowadays, these places are somewhat at the margins but they’re still there, and they need your business. Second-hand and independent book shops. Vinyl shops. Geek shops with names like Forbidden Planet or Plan 9 - half comic-book stores, half shrines. Flea-pit bars with local bands or cover bands. Jazz clubs where something new is being created every night. Local radio. Experimental theatre. Art-house cinemas. Even just your plain old local libraries.

These places are utterly essential to intellectual life. They enable human contact, cultural connection, the magical threads that help the discovery of life-changing art. And they’re all the more crucial because they’re not profit-driven but coming from a place of sheer enthusiasm. They are not, as the phrase goes, scalable. But that’s why they matter. You can’t algorithmically reproduce the joy of crate-digging, the thrill of a chance recommendation, or the hush that falls over a tiny theatre when the lights go down. These spaces resist efficiency. They create moments. And that makes them dangerous, precious, and deeply human.

Places like these created episodes in my life that I treasure. Going to a second-hand record sale and finding the first album by The Clash in mint condition for £2. Reading about Morrissey in Select magazine and then finding The Smiths’ compilation Best Of, Volume 1 in the library when I was 16 - just the right age for their potent brand of literary lyricism. Browsing charity shops and finding excellent hardback books like A Passage To India or the Ted Morgan biography of William Burroughs for less than a quid each. The owner of a vinyl shop helping me find Damned! Damned! Damned!, which I still think is the greatest punk album of them all. Watching Evil Dead II in a tiny cinema and everyone laughing themselves sick. Discovering brilliant writers like Edmund White and Leszek Kołakowski in independent bookshops. Seeing a Guns N’ Roses tribute band in a scuzzy live music bar playing a fucking wild set and enjoying myself more than I ever would at their reunion tour. (Someone tried to hit the bass player, who thumped him with his guitar. The night seemed like it might go awry, but a friend and I went down in front of the stage and responded to everything the band did with huge energy, and the whole gig took off like a rocket. It was awesome). Seeing Irvine Welsh give a reading, not at a university or bookshop, but in a nightclub.

Times like these matter more. They feel real, unique. You’re not sitting back waiting for a stadium band to entertain you; you’re part of the moment, and as always, the more you bring, the more you get from it.

It’s like the difference between participation and passive consumption. Kurt Cobain in one of his final interviews reflected on how he preferred shopping when poor, going through junk shops because “you might find a treasure that’s much more meaningful for you”. How right he was. Even when wealthy, he knew that culture is best when not curated or spoon-fed. It takes work, but from that work comes so much more meaning and delight.

But even within mainstream media, there is much we can do to foster new talent. Readings from emerging authors, thinkers, and poets. (Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim was featured on a BBC radio show for new writing before it was even published - imagine that now.) A greater openness to new cultures will help, too - South Korea has been producing some of the world’s best pop culture for years now, in films like Oldboy and Parasite, while Everything Everywhere All At Once was a great insight into the Chinese diaspora. Just like My Beautiful Laundrette was for the Indian community in London in the early 1990s. Interviews with rising stars, not the entrenched elite. Music sessions for fledgling bands - think of the astonishing richness of John Peel’s sessions.

We should treat obscurity not as a flaw but as an opportunity. Regional writers, for example, aren’t just small-time scribblers: they reveal the true diversity of voice in this country. Commission work that takes risks. (A new Netflix show Dept Q. has this outline: “A brash but brilliant cop becomes head of a new police department, where he leads an unlikely team of misfits in solving Edinburgh's cold cases.” What a brainstorming meeting that must have been). Give column inches and airtime to those without PR teams. Bring back the old model of cultural curation as discovery. It used to be the job of a magazine editor or a TV booker to seek out and champion the raw, the new, the unexpected. (BBC DJ Jo Whiley, for example, was the researcher who got Nirvana onto The Word in 1991, just as they were breaking. It’s TV gold.) Now, it’s too often about chasing what already has buzz. That cycle has to be broken. Algorithms don’t know what we need. People do.

8. Conclusion: Clear the Pipes or Die

Every culture has its own metabolism. Some, like punk, are a flash in the pan; some stick around for decades, like the blues; others remain part of the palette, like surrealism. That’s fine. But the danger now is that the metabolism has stalled. We haven’t been flushing out the past. It’s lingering endlessly in the system, metastasised by corporate laziness and risk-aversion.

Modern pop culture has become something we endure, not something that enhances the human spirit. It’s a kind of artistic sewage system with no exit. But when nothing can be cleared, nothing can grow. What we end up with isn’t heritage but dead weight, systemic blockage.

If we want a vibrant culture, we have to discard the idea that everything must last forever. We need the occasional artistic bowel movement. We need to make space for and to respect the initial fumblings of creatives. We need to support the small labels and studios making daring, risky new content, and stop watching dross pumped out by cultural barons just because it’s got a recognisable name. And we need to make sure we have spaces for art that allow human connection. Otherwise, we’re just clogging the shit-pipes of culture and choking on our own waste.

If you liked reading this, please share!

As I fellow Pink Floyd fan I keep asking myself: will there ever be another Dark Side of the Moon? Not the REDUX by Roger Waters which was a bit strange for me (not bad just weird). Will AI make something that great? I hope not. Or maybe something very good will be release and I will hate it because I became old? Maybe we are not stuck culturally, it is just that movies and books are not interesting anymore in this fast paced online culture. Maybe the new cultural product are so alien to us we can’t even comprehend. Look at what kids are into these days (Skibid Toilet?) I asked my 12 years old cousin what kind of music he liked and he told me that it was the soundtrack of a RPG game called Undertale (it’s good music, elaborate, but I could never have guessed that answer).

So I think maybe culture is evolving into something really strange to us and the old media is stuck in a loop. Maybe that happened before. Have you seen that video of tribal people listening to pop music for the first time? Maybe that’s us when the next Dark Side of the Moon comes in.

Thanks for the text it was a great read!

This situation is largely driven by our delirious copyright system.

Media companies "harvest" old intellectual property precisely because society grants them this rent on 50+ year old IPs, rather than letting it go into the public domain. It's not surprising that new creation is not prioritized when this rent seeking is protected and enforced by our courts and police.

When I write something like that, I sometimes get creatives coming at me for trying to take their lunch. Let's be clear: the vast majority of artists will never get any payments significance on 20+ year old work they produced. Almost all of this rent goes to giant media conglomerates and a select few royalty like Beyoncé or Paul McCartney. The average artist defending the ridiculous 100 year long copyright is as clueless as working class people defending Trump tax cuts without realizing that they are only getting breadcrumbs compared to the super rich.