Snooker At The End Of The World - Part 2

Genius and Decline: O’Sullivan, China’s Rise, and Britain’s Broken Pipeline

The O’Sullivan Ascendancy

No Golden Era lasts forever. Snooker’s was undone by the rise of football as the main working-class sport then the banning of cigarette advertising in 2005. In 1996, the prize for a 147 maximum break reached £147,000, having been around half that (£80,000) a decade earlier. By 2016 a maximum earned just £20,000. Some tournaments no longer even awarded specific prizes for getting a 147, just giving the prize to the highest break in the tournament.

The shining talent of the 2000s and 2010s was Ronnie O’Sullivan, who in terms of sheer ability was so far beyond everyone else it seemed he would dominate as Davis and Hendry had. (Hendry’s decline was remarkably swift, after winning a last world championship in 1999, as the yips took hold. It’s probably easiest just to say that such immense dedication blew some synapse in his brain).

O’Sullivan had it all: poster-boy dark good looks; ambidextrous ability (he could play with his weaker left hand as well as most pros could with their dominant); the ability to line up shots in fractions of a second where others stood and pondered; and a backstory that titillated the tabloids and gave pundits plenty to chew on - his father serving a sentence for murder. When he first played left-handed, other professionals thought he was mocking them. Confrontation with talent of a vastly superior order can feel insulting. Suddenly you feel human, vulnerable. In Ronnie, the dangerous aura of Alex Higgins met the ferocious attacking precision of Stephen Hendry. The 308-second 147 in 1997 both announced his arrival as a player of spectacular ability and raised what was possible in the game. But while he won that first round match, he lost in the second round to journeyman Darren Morgan.

O’Sullivan’s main rival was himself: early on, he plainly lacked the psychological strength to get him through the tough, bitty periods in the way that Hendry or especially Davis could. Slow frames made him visibly suffer, like a prize racehorse trapped in a stall. He was depressive, mercurial. No other player has simply walked out of a match as O’Sullivan did against Stephen Hendry, in their 2006 UK Championship quarter-final. “I'm a perfectionist when it comes to my game and today I got so annoyed with myself that I lost my patience and walked away from a game that, with hindsight, I should have continued,” he said afterwards, giving a vivid snapshot of his mental frailties. This helps explains why it took Ronnie 30 years to accumulate the seven World Championships that Hendry did in just thirteen.

Yet watching O’Sullivan in spate is a thing of spectacular magnificence. It is like watching Shakespeare write a soliloquy without revisions in real time, or Mozart casually improvise a sonata between drinks. There’s so little friction between thought and execution that the risk, the courage, the technical difficulty, all disappear. Maybe that’s why we don’t talk about Ronnie’s bravery. Because when genius looks effortless, effort becomes invisible. It’s tempting to think of genius as spontaneous, instinctive, even untutored.

But the greatest artists know better. Shakespeare didn’t just write beautifully about the human condition; he obsessed over the metrical inversions, the caesuras, the end-stopped lines that made the meaning sing. The Beatles didn’t just toss off “I Am the Walrus” as some psychedelic freak-out: they layered it with complex arrangements, surrealist structures, and studio innovations that other bands still regularly borrow. Using the studio as an instrument liberated them into even greater levels of musical innovation. These details are why people still delight in them decades or even centuries later. Because there’s always more to discover, more to enjoy. Genius is in the details.

And that’s what Ronnie O’Sullivan discovered. The difficult table wasn’t a constraint but a canvas to display further forms of perfection. Safety play, snookers, long tactical duels - he learned to find joy in doing them better than everyone else. When he tucks the cue ball tight behind the black in a five-cushion snooker, or escapes a snooker with a trajectory no one else saw, he’s not pausing the potting magic - he’s deepening it by crafting the variable geometry of resistance.

If you want to understand O’Sullivan’s greatness, watch the 92 he made against Ali Carter in the final of the 2014 World Championship. The reds are tight against cushions; the black is confined by four reds down at the bottom; the baulk colours are splayed out in the top half of the table; only the blue is on its spot. Willie Thorne commentating says, “He’ll do well to get above 20 from here.” Thorne, a wise old former pro, is no fool. But O’Sullivan delights in turning his gifts to problems beyond every other snooker player, and what he does here is breathtaking.

He starts by clearing the reds at the top of the table, and potting the baulk colours. Then he takes a few reds in the middle of the table, alternating with blues. With two reds on the bottom right cushion with the pink, and four reds among the black on the bottom, the obvious shot would be to go in from the blue to the black, and so break up that cluster. However, O’Sullivan goes for the red on the bottom left, planning to come back up for the blue. He needs to be above the blue to bring the cue ball down to the reds, but he hits the knuckle and ends straight on it. (“How does he win the frame now?” Thorne says). So he hits a sublime long brown and takes the cue ball off three cushions to finish near perfect on a red into the bottom right corner. When I say near perfect I don’t mean that he hadn’t lined the next pot nicely. He wanted to be slightly below the red so the angle would bring it up for the blue, but he is straight on it. However, he has the cue power to apply backspin and side to bring it up flawlessly above the blue.

Now he can finally hit those reds and black, no? Ninety-nine players out of a hundred would. The angle on the blue is perfect. The black ball, those luscious seven points, is a siren. Instead, he hits the cue ball with huge side so it evades those balls, bounces off the bottom cushion, swerves right and dislodges the reds around the pink. Now he can pot those two reds, and after the second hits another tremendous long brown, again coming off three cushions and finally dislodging the remaining two reds around the black. And from that he clears up. It is an astonishing display of instantaneous advanced calculation and unerring technical ability - the combination of the two being what we call genius.

Mid-career O’Sullivan has numerous examples of sustained brilliance that simply astound viewers, even old commentators like Clive Virgo and Willie Thorne, who repeatedly run out of superlatives. Perhaps the most shattering example of this was his ruthless demolition of Stephen Hendry in 2008. Hendry had twice beaten him in world semi-finals – the second time, after some stupid comments from O’Sullivan that he would send Hendry back “to his sad little life in Scotland”. Duly needled, a declining Hendry pulled out a performance of vicious, sadistic concentration that by the end left O’Sullivan frustrated and whacking balls in hope like a novice.

But this time O’Sullivan got him. Although Hendry went 4-1 up, O’Sullivan countered with the most incredible run of frames ever seen at the Crucible, winning twelve in a row and playing like he was a different order of human being who had quite simply solved the problem of snooker. Difficult long pots are taken with utter ease. When breaking the pack of reds, they spread like a flower. The cue ball goes exactly where he wants it to, to the centimetre. Hendry had once destroyed rivals by his mere presence. Here he was reduced to a forlorn figure scowling in a chair.

But for O’Sullivan at his most fluent, the five-minute 147 is the high-water mark: a break so fluid, so faultless, it may never be equalled. Most of us, at some point, have felt “in the zone” — at work, in play, in moments when conscious thought steps aside and everything flows. But this was 308 seconds of something else entirely: a sustained period of utter elevation. It is like being carried by angels. Every positional shot is superb. Every cannon or nudge is mathematically calibrated. Every pack break is exquisitely weighted. He’s lining up the next shot before the black has even been replaced. O’Sullivan was not just in the zone. He was among the gods, and they were watching in astonishment.

But even a miraculous player like O’Sullivan cannot carry a game forever. If snooker is to thrive, it needs not just O’Sullivan’s artistry, but new spaces, new players, and new cultures.

The Rise of China

Snooker has long been dominated by British players. There have been players from Asia in the top 32 – James Wattana from Thailand, Marco Fu from Hong Kong, and more recently Ding Junhui from China was often tipped as a potential world champions. But until 2022, there had been only three world champions from outside the UK – Cliff Thorburn, Ken Docherty and the Australian Neil Robertson. But in the last three years, it has been won by a Belgian, Luca Brecel, and a Chinese, Zhao Xintong. A brief glimpse at the rankings shows the rise of China: in the top 32 world rankings, there are ten Chinese players, second only to England with 15. Rather incredibly, former strongholds Scotland and Wales have only two each.

Snooker has been big in China for a long time, with Stephen Hendry having been an ambassador for the game there for over a decade. Ding Junhui was the first player to win a major tournament, taking the 2005 China Open at the age of 18, and he went on to beat Hendry in the UK Championship later that same year. His success lit the spark. For a generation of Chinese youngsters, snooker suddenly became a route to global recognition – televised, glamorous, and achievable with enough hours on the baize.

Chinese players have been steadily rising up the rankings since, though progress has not been without setbacks. The most serious came with the 2022–23 match-fixing scandal, the biggest disciplinary case in the sport’s history. Following a WPBSA investigation, ten Chinese professionals were banned for fixing or conspiring to fix matches. Among them were Yan Bingtao, the 2021 Masters champion, banned for five years, and Zhao Xintong, the 2021 UK Champion and one of the brightest young stars, banned for 20 months. Others, including Liang Wenbo, Lu Ning, and Chen Zifan, received even longer suspensions, in some cases lifetime bans.

The scandal was a body blow, though not all bans were for directly throwing matches: Zhao Xintong’s was for “being a party to another player fixing two games and betting on matches himself”. However, these were not fringe players – they were the very talents tipped to take over from Ding Junhui and establish China as a permanent powerhouse. For critics, it confirmed their suspicion that Chinese snooker was fragile, with a weak culture of professionalism. Yet it is also telling how the scandal was handled. The WPBSA pursued the inquiry aggressively, and the Chinese authorities cooperated fully. Unlike in some other sports, the offenders were not quietly shielded; they were made examples of. And crucially, the pipeline of talent is broad enough that new names quickly began to fill the vacuum: Si Jiahui’s run to the 2023 World Championship semi-final showed that China’s talent pool is genuinely deep.

Zhao Xintong’s path to victory in the 2025 world championship was remarkable: not only was he only the third winner ever to come through the qualifiers (after Terry Griffiths in 1979 and Shaun Murphy in 2005), but having only recently returned to the game in September 2024 following his ban, he had to play not one but four qualifying matches. And having only recently returned to the tour, he was still officially an amateur, making him only the fourth to even play at the Crucible.

His route to the final involved beating two of the world’s most decorated players. But Zhao destroyed Ronnie O’Sullivan in the semi-final, winning the second session 8-0 on the way to a 17-7 victory. He then nervelessly beat Mark Williams (playing his fifth final) 18-12 to become world champion. Zhao’s triumph was a personal triumph, of course, but also hugely symbolic: not only a possible last hurrah for the fabled “Class of ’92” - O’Sullivan, Williams, and Higgins - but also the clearest marker of Chinese ascendancy in snooker. And yet, the very fact that three men in their fifties still stand as the game’s dominant figures reveals a deeper problem: the British talent pipeline has dried up.

A Cultural Litmus Paper

Having lived and worked in China for fifteen years, I’d like to offer some speculations as to why China is rising and the UK declining when it comes to producing snooker talent. The issue isn’t simply population, for the Chinese national team still fails to qualify for football World Cups. That is an entire book-long story in itself, but suffice it to say just having the numbers and even ample finances is not enough. The issue is about culture and space - the extent to which a society fosters, accommodates, and values the conditions for mastery.

Firstly, snooker obviously demands intensive practice. We’re talking eight-to-ten hours a day, full-time, monastic devotion to the baize. Stephen Hendry writes eloquently in his autobiography how painful moving to professional level practice was, but how essential it was to elevating his game to winning tournaments. I sometimes wonder if, in the UK, there is less cultural space for such intensities. We still applaud sporting and artistic brilliance, but pursuits that require long, disciplined graft — chess, programming, poetry, Dungeons & Dragons, electronic music — are often treated as eccentric, even nerdy. Too often, their enthusiasts feel the need to apologise for caring.

This is not to say Britain lacks talent or hard work - far from it - but that our cultural vocabulary for celebrating discipline has thinned. Focus, patience, and the long, unglamorous work of mastery now struggle to compete with the appeal of instant gratification. It wasn’t always like this. Channel 4 once broadcast the Nigel Short–Garry Kasparov chess match live. Play for Today drew national audiences for serious drama, and Despatch Box was a far more mature and serious TV show on politics than The Daily Politics. Martin Amis recalls in Experience how Philip Larkin’s anthology of twentieth-century verse sparked fierce, public debate in 1973. That kind of intellectual engagement has become rarer. And in 2025, it is telling that increasing numbers of UK and US undergraduates say they cannot read entire books. By contrast, when I taught a top-set English class in a Chinese high school, in a single year we tackled Wilde, Forster, Shakespeare, Golding, lots of poetry, and creative writing. I adored that class. They worked their socks off.

I’m not trying to claim some kind of essentialism - to say that Chinese people work harder than lazy Europeans. I have certainly taught numerous lazy Chinese students. But I know that the Chinese who want to succeed understand that dedication is non-negotiable. They know progress is perspiration. Whereas the gifted people I’ve met in the UK have so often been reluctant to pursue their talent with the necessary devotion. Take myself as an example. At 15, I had a creative breakthrough in my writing. But I lacked the mentality and social encouragement to pursue it. It wasn’t until I moved to China that I found a writing opening. And once I had the opportunity, I worked like hell, doing columns, copy-editing, event coverage. In eighteen months I went from freelance contributor to editing a Beijing magazine. This wasn’t quite potting balls at dawn or running marathons before school, but it taught me what the Chinese already knew: talent without effort is nothing. In China, this is basic stuff. Competition is ferocious in every area. The acceptance rate at Tsinghua University, China’s equivalent of Oxford or MIT, is estimated at 0.1–0.3%. By comparison, Harvard accepts around 3.5%. The university entrance exam, the gaokao, is a national ordeal. Students are expected to study 16 to 18 hours a day for it. That’s not hyperbole.

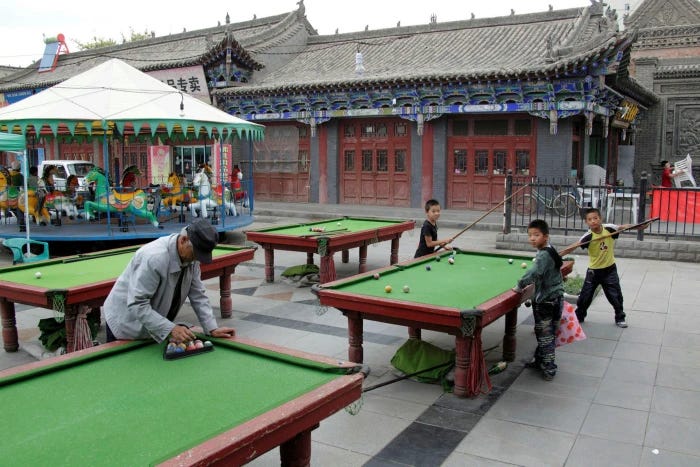

The other key factor is space. China has greatly overbuilt in the last twenty years. A residential and commercial bubble has left more buildings than businesses, which means commercial space is plentiful - and pool halls are everywhere. There’s one in every neighbourhood, pretty much. When I first arrived in China in 2007, the local one was a smoky, dank venue with actual spittoons, ageing tables and toilets that defy polite description. (We called it “the beer pit”, but that didn’t stop me playing eight hours a day there when I could). Nowadays they are generally clean, warm, with new tables, decent cues and unchipped balls. Normally there are around 10 pool tables and two or three snooker tables in the average club. Enough for everyone. Prices are reasonable, around RMB30 (£3.35) per hour. Alcohol seems to have vanished from most of them, for whatever reason. People come to play, not piss about. And they do.

The contrast with the UK is profound. Jason Ferguson, chairman of the WPBSA (the world snooker ruling body), noted in a recent interview with Stephen Hendry that the main issue affecting the game is facilities, and that “the average club is under threat of closure at all times. That is not because they're not busy. It's not because it's not a good business. It's because every landlord wants to turn it into flats.” Consequently, the WPBSA have been lobbying the government to protect some clubs as “buildings of community interest, and the number has actually grown each year in the past two years.”

While praiseworthy, that is from a very low ebb. In the 1990s, venue operator Rileys had 165 snooker, pool and sports venues across the UK; its website today (August 2025) lists only fifteen. In “Changing Britain through the frame of snooker” (2024), Dr Alex Rhys-Taylor notes: “A survey of the last two year’s local news stories reveal more recent cases of doors being shuttered in Romford, Stoke, Glasgow, Belfast, Grays, Brighton, Stockport, Bury, Hornchurch, Southampton and Dennistoun. Online message boards report stories of further closures from Nottingham, Milton Keynes, Belfast, Edinburgh, Stevenage and Luton.”

We have so much to re-learn as a society. The issue is simple. Talent grows when it has non-commercial space in which to develop. Non-commercial space is the precondition of mastery. If we reduce the fabric of our villages, towns and cities to only profit centres, we are choking the lifeblood of every single cultural activity. The shuttering and gentrification of all those working men’s clubs, leisure centres and village halls has caused a slow cultural collapse. No wonder people in Britain seem increasingly unhappy. Orwell once noted that the British were a nation of hobbyists, but we increasingly can’t find the spaces for them. Lottery funding might have transformed athletics, but that requires dedicated facilities and funding. Snooker however has been left to itself and so has withered on the vine, like all other activities not at heart moneymaking pursuits. Even pool tables in pubs are becoming harder to find.

If we accept that property is only about commercial value rather than social utility, we are going to make UK towns and cities deserts of opportunity, not just for snooker but for anything sustaining communities. An endless vista of atomised, fragmented individuals cut off from each other in commuter towns or low-density cities, only to work, eat and sleep. What a grim thought.

Coda

In Britain, success in the classroom has long carried a faint whiff of embarrassment. To stand out is to show off; to work hard is to invite suspicion. In China, by contrast, the social climate tends to normalise striving: almost all students face strong parental pressure to get on, and afterschool clubs or extra classes are seen as part of the landscape rather than “pushy.” This is not about innate differences in work ethic — there are plenty of lazy Chinese students, just as there are plenty of diligent British ones — but about the messages young people receive from the institutions and families around them. One culture encourages effort as a collective norm; the other often makes ambition feel like a solitary eccentricity.

What I can say anecdotally is that I once believed that benevolent neglect was the right way to raise children, trusting that they would find their own hobbies, but I now think otherwise. Because children generally do not form the muscles for sustained effort by themselves. You have to guide them. And so it is with the development of talent generally. You might get the odd untutored Shakespeare every now and then, but even Mozart was hot-housed into his genius by his musician father. In China, social conditions make it common to see people striving to develop their abilities. Ambition and effort tend to be reinforced by families, schools, and peers — and in that environment, talent has a better chance to rise.

When I go to snooker halls in China, I see players of all abilities. They are having fun, but they are serious, too. In Britain, by contrast, the tables are vanishing, players pushed out by landlords and indifference. Snooker is thus not just a sport but a cultural litmus paper. In the UK, we allow talent to wither by starving it of space and seriousness. In China, there is still an appetite for mastery, for the slow accumulation of skill that turns a hobby into art. That is why, for all his genius, Ronnie O’Sullivan may be less the future of snooker than its epitaph: the last great flowering of a culture that once produced greatness but now struggles to sustain it, as reflected in the fading of working-class footballers, politicians, and musicians.

The rise of China shows, starkly, what happens when a society encourages young people to excel. That lesson extends far beyond the baize. It is about whether we value patience, effort, and community over short-term profit and private space. The future of snooker is hence not just a sporting question, but a question of what kind of culture we want to be.