Snooker At The End of World - Part 1

Inside the Drama, Discipline, and Delicacy of Snooker

(This is the first part of a longer article I’ve written on snooker. Fans of sports writing may well be familiar with String Theory and Roger Federer as Religious Experience, by David Foster Wallace. Reading them made me want to try my hand at an equivalent on snooker. That might sound demented, but let me know what you think. The second part will be published next week).

The Impossible Blue

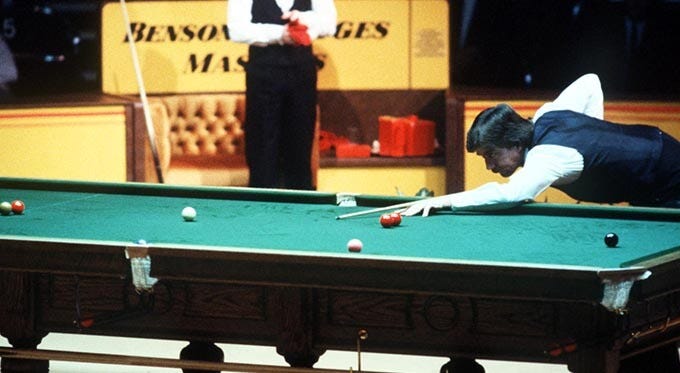

It’s 14th May 1982, the snooker world championship semi-final in the Crucible Theatre, Sheffield. The young contender Jimmy White is leading 15 frames to 14 against the firebrand Alex Higgins. White needs just to reach 16 frames to be through to his first final. He is leading by 59 points to 0 and wants just one more red ball to leave Higgins needing snookers – safety shots where you try to induce a foul shot from your opponent, thus costing them at least four points. White lines up a straightforward red to the bottom right corner – but misses it.

Higgins moves around the table like a panther. He has won the world championship once, in 1972, but been a finalist in 1976 and 1980. More than that, he has been the poster boy for the sport since his late teens, when his brand of devil-may-care snooker electrified a staid sport played in smoky halls and working men’s clubs. His nickname “Hurricane Higgins” is well deserved amidst the safety-first methods of men like Cliff “the Grinder” Thorburn and Ray Reardon, the former policeman who dominated the 1970s. By comparison Higgins is Hollywood. And he knows it.

But he only has one World Championship to his name, for example outmanoeuvred by Thorburn in 1980 by being too gung-ho in his shot selection. The two men detest each other, Higgins in an earlier match having pretended not to hear Thorburn call a shot when the referee bizarrely missed it. Snooker is a gentleman’s game, but Higgins disdains niceties, for good and ill. To win again, however, Higgins has tightened up his game, refusing to take kamikaze pots and playing safety shots more effectively, but White is a remarkable player in his own right, and there’s little doubt he’ll be in a final soon enough.

There are six reds remaining, giving a potential score of 75. Each red earns you the right to a colour - from the modest yellow (2 points) to the majestic black (7) - and the cycle continues until reds are gone. Then the colours, in order. The black ball normally sits at the bottom of the table, under the red balls. However, at this time the black is high up the table, near the brown ball, and one of the reds is tight up against the top left cushion, making it harder to pot. Higgins knows he may well have to pot some lower value colours, thus making his task even harder. He may well need to pot every single remaining ball.

The white ball is just beneath the pink. He pots a straightforward red to the bottom left corner, but fluffs his positioning of the cue ball for his next shot. (The skill of snooker isn’t so much in potting – though that is far harder than you might think – but in positioning the cue ball for your next shot, through the correct use of angles, top spin, back spin, velocity, or side spin). The white is just above the pink ball, but Higgins can’t go for that; reds are blocking the way. The angle to the blue is pretty straight and hence deeply unpromising for getting in into a top corner pocket, while the baulk colours (yellow, brown and green, from left to right) are unpromisingly distant.

Most players would hit the green gently and bring the white to rest against the top (“baulk”) cushion, leaving White a difficult shot. Instead Higgins pots the green and uses left-hand side on the cue ball to bring it round and dislodge the red on the cushion. He then pots a tricky red near the bottom right pocket, but again bungles his position, the cue ball coming up next to the yellow. But the black is near, so he pulls out a superb long pot to sink it. He then pots a tricky red into the left centre pocket, and brings the white ball almost exactly back to where it was before he took on that green.

But now he needs the points. Baulk colours won’t suffice. You can see him calculating. So now Higgins unleashes perhaps the single greatest shot in snooker history. While hampered by the pink, he absolutely leathers the blue into the top right pocket, but he hits the white with so much left-hand side that it comes up off the top-left cushion and comes back down the table, underneath the reds. No matter how many times I watch it, I can’t believe the geometry of the shot. It is not perfect – Higgins wanted the white to be on the right of the reds, not underneath them, but he’s hit it too hard – but in its imagination, courage, and sheer devilry, few shots come anywhere close.

Analysing the shot only adds to its grandeur. The electric pace makes it so much harder – with greater velocity you need greater accuracy, because a fast ball can bounce back off pockets that might have yielded if played slowly. The side spin on the cue ball also complicates things, because you’re hitting it off-centre, which pushes it a few degrees off and so you have to recalibrate the potting angle. Given these three variables of pace, angle and spin, it is incredible not just how Higgins calculated them all in his head but how he implemented them so precisely and so thrillingly.

The white now sits just right of the black ball at the bottom of the table, so Higgins pulls out another exceptional long shot to pot a red into the top right pocket. And from there, the frame is relatively straightforward – not easy, because there’s still huge pressure on Higgins, who cannot miss a shot, but now all the balls are in conventional places – and he clears up to take the frame, 69-59.

He then takes the final frame to win the semi-final, and wins the final against an aging Ray Reardon. However, it is the “impossible break” of 69 which lives on folk memory and YouTube videos. (Particularly that blue. Go and watch it). But in hindsight, that 1982 championship felt like the end of something. Higgins wasn’t just winning - he was defying everything the sport was becoming. A new order had asserted itself: clean-cut, methodical, machine-like. His triumph was the final, glorious act of the old snooker world - wild, unruly, brilliant - before the reign of Steve Davis.

The Thrill of Snooker

I enjoy watching many sports. Each poses different challenges and it can be enthralling to see teams or individuals find ways to surmount them. Football at its best can be balletic, beautifully geometric, and also pulsatingly physical. Tennis – to respond to David Foster Wallace - can be beautiful in its rallies and briefly thrilling in its aces, but it can also be a slog if service games are too strong to return. Only Federer made it graceful again. Badminton requires poise and nuance and deftness and power all at once. Basketball can be as thrilling, but the sheer volume of scoring can make each point feel cheap. Cricket can feel too sedate but when it warms up and stumps fall and batsmen take their stand against ferocious bowling, it too can be exciting.

Snooker, however, I find endlessly fascinating. It is both intensely psychological and mathematically precise. It requires laser focus, supreme hand-eye coordination, enormous courage, and immense psychological fortitude. Played in silence, it is the most remorseless of all sports. When your opponent is in, you can do nothing. And what it lacks in physicality, it more than makes up in the gladiatorial aspect of the game: the way players assert dominance, the way they fight in three dimensions simultaneously – against the balls, against their opponents, and against themselves. It is part art, part warfare, part Rorschach test.

And like every sport, an examination of its play reveals a great deal about player psychology as well as the social and cultural conditions that enabled these players to thrive. Snooker was once a game of Britain and its former white colonies. But two of the last three world championships have been won from outside those countries. Former strongholds like Scotland and Wales are not delivering the talents they once did. Will the sport have to change? Will it become fully internationalised? Whither snooker?

Snooker As Self-Portrait

On TV, the snooker table looks about the size of a pool table, perhaps a little larger. In real life it is a swimming pool of green baize. It measures six feet by twelve feet – twice as long as a six-foot man. It is immense. Pool tables by comparison are significantly smaller, with standard bar tables measuring eight by four, which doesn’t sound much smaller, but contains 32 square feet compared to the 72 square feet of the snooker table. A good bit less than half. So we’re talking about a really big fucking table.

The mathematics are fairly simple: there are a maximum of 147 points on the table. You therefore need to get at least 74 points to win a frame (unless you concede points from snookers). But within that basic premise lies an entire culture of stress points and thresholds. The breakoff shot, for example, takes the cue ball off the left of the reds, off the bottom left cushions and back behind off the top right cushion to nestle hopefully near baulk. But in recent years long potting has improved so much that any stray red ball is vulnerable, letting your opponent in to start a large break. (Some players, like Mark Williams, even play devious shots off the bottom cushion to nestle against the bottom of the pack, but this is generally felt to be unsporting).

Similarly, if you are in amongst the reds and the black is in play, this is optimum territory for building a large break. Red, black, red, black. But what you may not realise is how precise you have to be with the cue ball. The angle at which the cue ball strikes the object ball determines where it goes next - and even a few millimetres can transform the entire layout. If you're on the "wrong side" of the object ball, the cue ball travels away from the ideal zone, often forcing a much harder shot next. That’s why professionals talk about being “on the right side” - it’s not just about potting the ball in front of you, but shaping the next one, and the next. In snooker, the margin between perfection and failure isn’t inches. It’s fractions of a degree. Get the wrong side of the balls, and you may have to come up for a riskier blue or even green, requiring you to have a riskier long pot for the next red.

A further aspect is that snooker can destroy you psychologically in a way that few other sports can. In pool it’s rare to wait more than a few minutes before having a shot. In most team sports you’re competing directly against your opponent the entire time, doing the best you can whether in a scrum or table tennis rally. But in snooker you may be frozen out of the game for twenty minutes or more while your opponent racks up the points. You may mess up your next shot and be frozen out again – and again… There are very few players whom this does not affect. Even Ronnie O’Sullivan, often called the greatest snooker player of all time, is vulnerable to it. Opponents like Peter Ebdon and Graham Dott took advantage of this rare weakness, slowing their games down to the glacial so that O’Sullivan, who can line up shots in fractions of a second, plainly suffered agonies of impatience. Mark Williams and John Higgins (no relation to Alex) are perhaps the best at handling this. That’s perhaps why they’ve been playing at the top level for almost thirty years.

Most sports are about noise, momentum and drama: Formula One, boxing, basketball, even cricket. But snooker is played in exquisite, terrifying silence. There is no coaching between frames. Players sit in utter isolation. Fans are almost always respectful of the need for silence when a player is at the table; breaches do occur between significant pots, through applause and cries of encouragement, but referees do an excellent job in policing the monasterial silence when play is in hand. There is no hiding place for players, no team mates or coaches or crowd ambience. It is you, and the balls, and your opponent.

The best players thrive on this. Stephen Hendry, for my money the greatest player ever, was deliberately ice-cold to fellow professionals. He moved around the table like a lion, utterly certain of his jungle dominance. His facial expressions betrayed nothing except the intensity of his focus. From 1992 to 1996, he won the world championship five times in a row, once with a broken arm. Steve Davis, who dominated the 1980s, was sarcastically nicknamed “Interesting” because of his ruthless will to win. Not for him the smoking, drinking and crowd-pleasing shots of the pool hall men. Davis was there to dominate. His poise, his perfect tailoring, his expressionless focus, all said: Nothing will stop me. Especially you.

These men thrived on pressure. They were swashbuckling in a subtle way. The theatrics of Alex Higgins was not for them. They destroyed rivals before even getting on the table. Against Higgins, twitching, smoking and drinking, you always had a chance. Davis then Hendry took the game to new levels, Davis through professionalism and exquisite tactical play, Hendry through attacking ferocity and remorseless concentration. But since Hendry, no player has dominated the sport in the same way. O’Sullivan has matched his record number of world championships (seven), but over a 21-year period.

Yet the silence, the scale, the millimetric precision: these are only part of what makes snooker so psychologically rich, so utterly absorbing. It is not a sport for adrenaline junkies or casual thrill-seekers. It is a game of tension - of failure looming with every shot, of pressure that accumulates through the slow tightening of mental screws. What makes the game so quietly brutal is the same thing that makes it beautiful: the room for self-expression within relentless constraint. In the hands of Hendry, snooker was a conquered empire of geometry; in the hands of Higgins, a bar fight dressed up as ballet; to O’Sullivan, it is his inestimable talent getting the measure every scenario; to Mark Selby, it is about his relentless will and drive. Because snooker, like any sport worth understanding, isn’t just about how it’s played. It’s about who plays it - and why.

*

The Golden Age

Snooker came from the smoky pool halls and working men’s clubs of a Britain that still had space for male hobbies. Not commercial areas but cultural spaces where you could play, relax, and interact with men usually of your own social level. But from 1977 snooker settled on one place for the World Championship – the unglamorous city of Sheffield, though fairly central within the UK. Popularity surged as first Pot Black came on BBC2, then as snooker matches were shown live. Sponsorship took off, too. The 1982 UK Classic was sponsored by Lada of all companies, but by 1984 the sponsors were brands like Embassy, Regal, bookies William Hill and Scottish brewer Tennants, mass-market brands reflecting high public interest.

The players at this time were a mixture of pool hall graduates and sleek 1980s professionals. Canadian Bill Webernick used to drink so much beer during matches – to calm his nerves – that he tried to claim it as a working expense. Alex Higgins smoked and drank constantly, a bag of twitching nerves until he became a sleek panther at the table. Jimmy White was pasty-faced like the young man stuck inside darkened East End pool halls that he was. Cliff Thorburn was a transitional figure, having come up through the school of hard knocks (early life in an orphanage, travelling across Canada playing for money) but adopting a style as unrelenting as granite.

The key modernising player was Steve Davis. While audience loved Higgins and his swashbuckling style, he could always miss an easy shot. You never knew. This probably only endeared him further to British audiences, which loves glorious failures. Davis meanwhile didn’t drink, didn’t smoke, didn’t interact with other players - and hoovered up the prizes with a look of supreme indifference. Higgins played with the stress of every shot visible. Davis thus took the sport away from the halls and into the commercial boom of the 1980s, his manager Barry Hearns fixing up sponsorships and licensing deals (for books, computer games, snooker cues, and the like) with such alacrity that Davis was the UK's highest paid sportsperson in the latter half of the 1980s.

But every new epoch leaves others behind. Though Alex Higgins got to the world-semi final in 1983, for the rest of his career he never got past the second round, and he only ever won one more tournament, the UK Championship in December 1983. (He must have delighted in beating Steve Davis, who he despised as much as he did Cliff Thorburn). Despite getting hairplugs to cover his increasing baldness, it was apparent that Higgins – his volatility, his disdain, his unruliness – weren’t what snooker wanted in the shiny new decades. In 1986 Higgins head-butted a tournament director and was fined £12,000 and banned from five tournaments, then in 1990, after losing a world championship first round match, he punched a tournament official in the abdomen before a press conference at which he announced his retirement, abusing the media as he left. For this he and other misdemeanours he was banned for 15 months. Alex Higgins might have made snooker but snooker could now do without him.

But this is to jump the gun. The rise of Davis brought in snooker’s 1980s Golden Age, where a cast of contrasting personalities gave everyone someone to cheer for. There was cuddly underdog Dennis Taylor, with his upside-down spectacles. There was the Welsh champion Terry Griffiths. There was Kirk Stevens, the man in white, with his 1980s mullet. There was Ray Reardon, still, his prominent widows peak having earned him the nickname Dracula. This was Cliff Thorburn, implacable as stone. There was Jimmy White, the people’s champion. This was snooker’s heroic age - not because the players were flawless, but because they were distinct. Each one brought his own style and his own demons. You could love Higgins’s madness, Davis’s ice, Taylor’s smile, Thorburn’s grit, White’s showmanship. And thanks to uninterrupted TV - still limited in channels, but vast in viewership – these players were icons. The baize wasn’t just a playing surface anymore; it was a stage for titanic duels.

If Higgins had played as if trapped in his own Greek tragedy, the drama was cleaner, brighter, staged in three-piece suits under the gleam of television lights. The sport had become a national obsession, its cast of champions as familiar as soap opera leads. Each player was more than an athlete; they were a character, their stories unfolding frame by frame in the hushed TV transmissions, until viewers could read them as easily as a tabloid’s front page. This was high drama in the age of colour TV, crowned by the golden age’s zenith — the astonishing final-ball shoot-out of the Davis–Taylor 1985 final, as watched by over 18 million who couldn’t go to bed until Taylor’s last-gasp triumph.

(Part two, on Ronnie O’Sullivan and the rise of China, will be published next week).

If you liked reading this, please share!