Pink Floyd: The Wall and the Three Ghosts of Subjectivity

Decoding The Bricks in the Wall

…Where we came in?

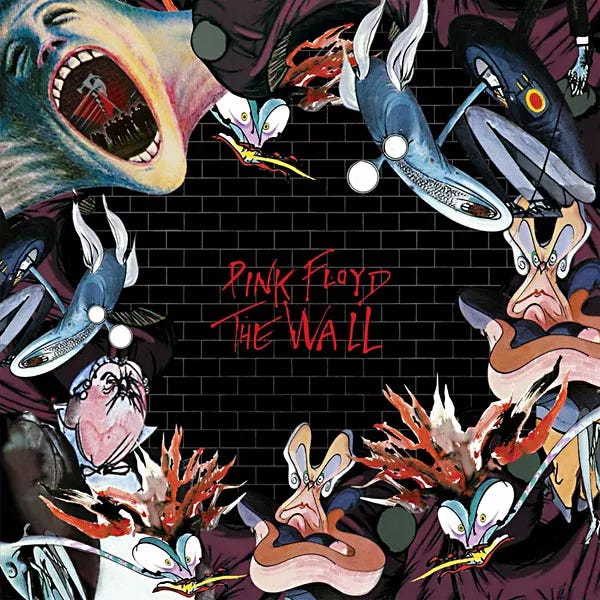

If art is, as Salvador Dalí said, “the persistence of memory”, then it is a haunting: an apparitional remnant lingering into the present. Among works that confront their own spectrality - The Marble Index by Nico, Closer by Joy Division, The Holy Bible, Nirvana Unplugged - few are as choked with ghosts as The Wall by Pink Floyd. Whether encountered as album, stage show or film, The Wall shows that haunting lies not in wailings or chain-rattlings but in trauma, alienation, and absence.

Over the course of ninety minutes, the movie Pink Floyd: The Wall (let’s stick to this version) is the ultimate rock opera, telling a larger story through song and image. But on a deeper level, one which critics miss because most stopped discussing rock music as art sometime in the 1980s, The Wall is a haunting from three particular ghosts. Just like in A Christmas Carol. But these particular ghosts are the three theorists who haunt the modern individual: Freud, the ghost of Christmas Past; Marx, the ghost of Christmas Present; and Derrida, the ghost of Christmas Future. Pink, the gestalt protagonist of the movie, like Scrooge is haunted by his past, present and future, and finally escapes following a judgement to an indeterminate future. The album says, “Isn’t this where we came in?”, taking us back to the beginning, but the movie suggests, through a brightened version of the song “Outside The Wall”, some kind of closure, when the “bleeding hearts and artists” have made their stand. Waters himself couldn’t decide: was it a cycle or redemption? Perhaps both. Or perhaps, as with all hauntings, the only certainty is recurrence.

Christmas Past: Freud

The Wall is a film deeply haunted by the past, in its most literal sense: by Roger Waters’ own biography. His writing steadily became more personal, from Dark Side to Wish You Were Here to Animals to The Wall. In the latter, he directly addresses his absent father (killed in action in 1944), overbearing mother, sadistic schoolteachers, and marriage breakup. All of these animate individual songs outlining their traumatic effect on Pink, and appear in “The Trial” as literal apparitions denying their own guilt. Each leaves their mark: the son denied a father (as in that terribly sad scene of young Pink trying to hold the hand of a random dad in a park), oppressed by a mother (who “might let you sing but won’t let you fly”), bullied by teachers who would “hurt the children any way they could”, and let down by a cheating wife (the international phone operator noticing, “See? It’s a man answering.”). Each scene is a Freudian primal trauma, leaving its mark on the adult Pink. Their ghosts live on in his mind, spectres continuing into the present.

And like Freudian ghosts, they insist on repetition. Abuse begets abuse. Teachers who bully children are themselves thrashed “within inches of their lives” by “their fat and psychopathic wives”. Self-loathing leads to violence, like spousal abuse – “I need you / To beat to a pulp on a Saturday night”. And while hotel room destruction had by the 1970s become part of the rock n’ roll legendarium, in “One Of My Turns” it sounds utterly grim, an auto-da-fe of self-hatred. Pink’s relationships are shattered, and fame sought in recompense. But women cannot be trusted, there is no home but an unmade hotel room, and colleagues abuse Pink for their own ends. The show must go on.

Freud suggests in Beyond The Pleasure Principle that we seek to repeat the most painful instances in our life, so that we can gain mastery over them. (Thus, for example, the survivor of sexual assault who wants to restage their trauma in an attempt at psychic control. These things happen). For the musician, repetition is both method and metaphor: practising chord shapes or changes again and again until technique replaces spontaneity. Repetition becomes mastery, but also alienation. You can hear this in the beautiful yet affectless classical guitar solo that concludes “Is There Anybody Out There?” It’s lovely, but without any emotion. So Pink becomes a musician not to express but to escape his feelings. I have become comfortably numb.

Christmas Present: Marx

You don’t have to have read Derrida to see spectres of Marx in the modern world. Alienation, commodification, spectacle and estrangement are practically synonymous with modern life. But these ghosts particularly haunt The Wall. Waters’ parents weren’t just socialists but Trotskyite activists, and that socialist worldview remained in him. He might have lusted after material signs of success like owning a Bentley, but he mocked bandmate Rick Wright for buying a country pile - until he got round to buying one himself.

Reconciling the two worldviews would prove impossible. In Dark Side, he offers understanding to all those damaged by the stresses of capitalism, but in the three great albums after that, his mood turns from condemnatory to vituperative. Animals is class hatred turned into allegory - pigs, dogs, sheep - and by The Wall that fury is turned inward, toward the commodification of the self. Pink, the character, is both product and producer: packaged, marketed and chewed up by the machine he fuels. He becomes both commodity and labourer, estranged from his work and from himself.

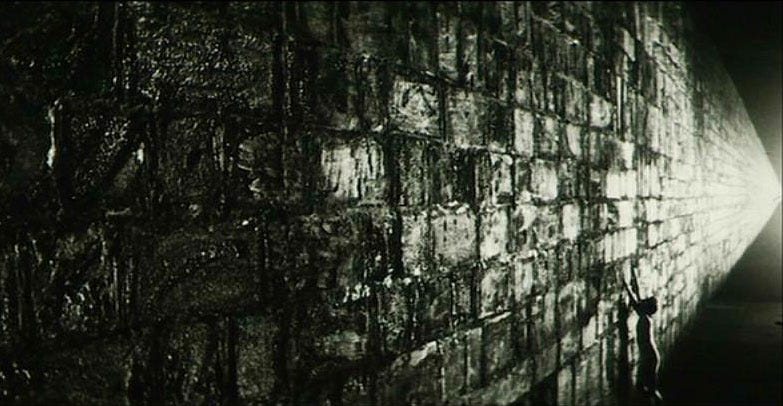

The Wall concerts were stunning dramatizations of this: the band playing behind a wall of bricks, hidden from their own audience, spectacle replacing presence. Debord’s Society of the Spectacle was published in 1967, but Waters didn’t need to have read it. He experienced it personally (most famously in Montreal in 1977), and with great artistry created a startling theatrical equivalent. Fans would pay not for connection but alienation and absence, and the disappearance of the band.

Marx describes alienation as the worker becoming estranged from their own labour. He wrote, “The object that labour produces, its product, stands opposed to it as something alien, as a power independent of the producer.” The worker becomes impoverished through his own creativity: “the more wealth he produces, the poorer he becomes in his inner life.” The Wall dramatises this aspect of Pink’s present relentlessly. He is a musician, but his music no longer belongs to him. His life is a staged performance of endless repetition, enforced by managers and promoters, estranged from any meaning he might once have intended. The show must go on, but the show does not belong to Pink. He is consumed, and his alienation packaged and sold back to the crowd.

This is why the fascist rally sequence in the film is so unnerving. It is not merely a critique of authoritarianism but of mass spectacle itself. The audience does not want Pink’s presence; they want his image, his role, his commodity-form. When Pink barks grotesque orders from the stage, the crowd roars in delight, as though their subjection were the product they’d paid for. Here, the ghost of Marx is unmistakable: the concert arena is transformed into a factory of alienation, every cheer greeting labour estranged from the self.

Christmas Future: Derrida

If Freud haunts The Wall with the weight of the past (the wounds of childhood and the persistence of trauma), and Marx shadows its present with alienation and commodification, then Derrida’s ghost reveals that identity, language, and even time are never whole. As Derrida wrote in Specters of Marx, “the future is always to come; it is that which is not yet and that which must remain unforeseeable, the coming of the other itself.” The future is not what comes next, but what can never fully arrive - the perpetual deferral of presence. Pink’s future is never settled. We never learn what lies outside the wall.

Like The Dark Side of the Moon six years earlier, The Wall has a poetic vocabulary based on binary oppositions. In Dark Side they include dark/light, us/them, with/without, sanity/lunacy, presence/absence. Whereas The Wall is more focused: inside/outside, and again sanity/lunacy and presence/absence. These oppositions invite a deconstructionist reading. The interiority of Pink becomes a prison; the outside is hell, and then escape. Similarly, Pink’s presence is always in doubt. Pink is not really here; he’s part of a “surrogate band”. As Derrida notes in Of Grammatology, presence is never self-identical; it is always deferred as part of a chain of signifiers pointing to an absent centre. “Hello? Is there anyone there?” asks his wife - though we can see Warhol-style portraits in the background, proof of having arrived. (But if you have arrived, where did you leave?) “Hello? Is there anybody in there?” echoes the corrupt doctor. Is there a platonic essence of Pink lurking inside? During the fascist rally sequence, even Pink disavows his presence: “Pink isn’t well, he’s back at the hotel,” he says, as though he himself wasn’t Pink. This is not how I am.

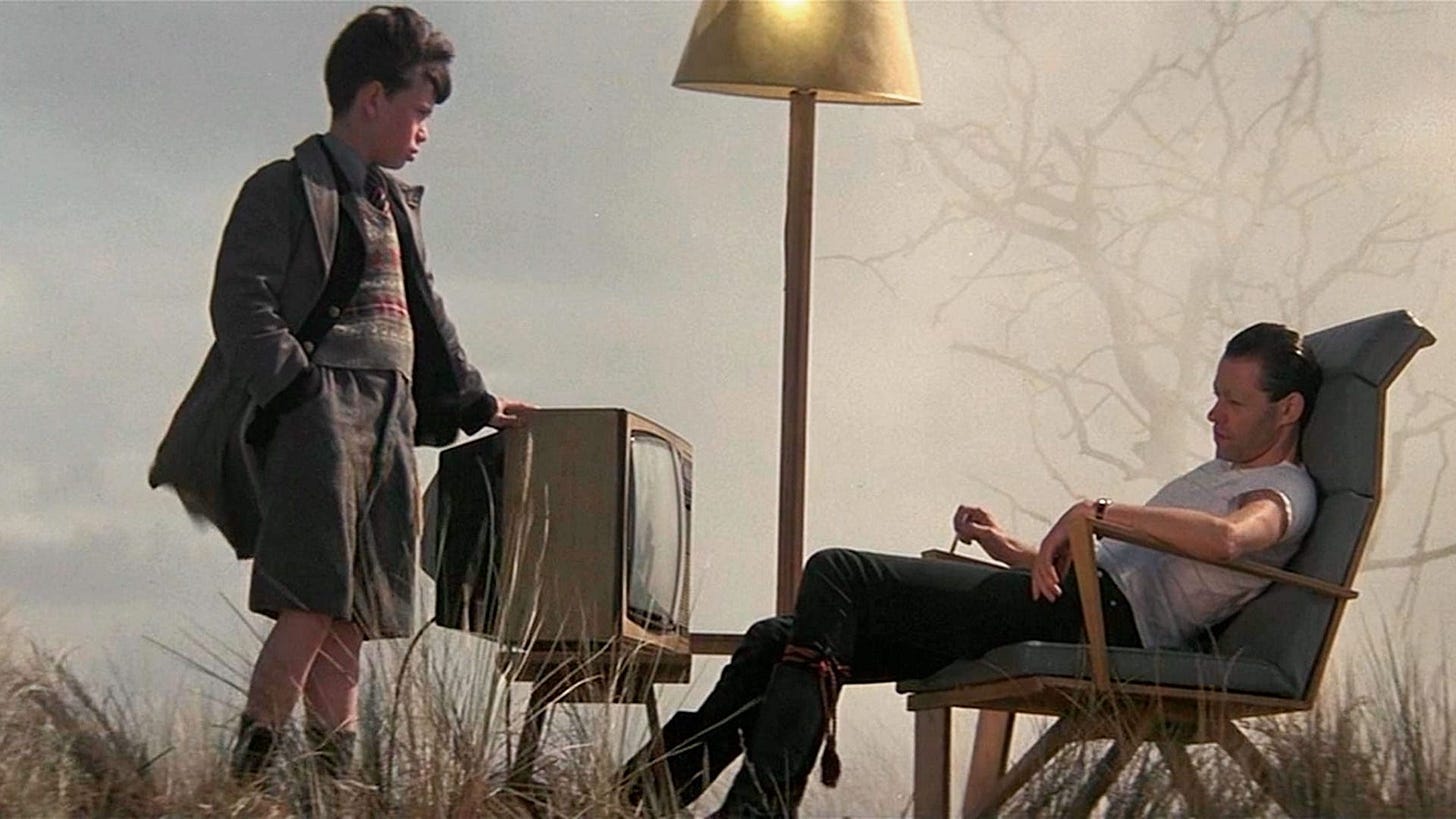

Similarly, The Wall could be viewed as Pink’s search for solidity - a father, a wife, a self. But throughout he finds only absences. Young Pink dresses in his father’s military uniform, and sees him - but only through a mirror. The reflection shows his own face. Fame is no replacement for the self, the movie satirising the vulgar ostentation of aftershow parties (the tour manager spitting out champagne), the loveless mutual exploitation of groupies (“Wanna take a baaaath?”), and the numbing fugue of the TV (with “thirteen channels of shit”) always on in the soulless hotel room. Pink’s wife offers no succour either: their flower-power wedding is washed away in the rain; she betrays him - pointedly, with a CND campaigner, as if seeking meaning in the engagement Pink rejects - and when he calls, seeking connection, there’s “nobody home.” Everywhere he looks, there are only ghosts.

While Waters admits it is largely autobiographical, another figure looms over The Wall. The ghost of Syd Barrett haunts the album and movie. Though he was still alive, Barrett’s absence looms larger than any presence. He is there and not there, simultaneously alive and erased, his breakdown written into every song Waters penned from “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” onwards. Barrett is the ultimate Derridean signifier in The Wall: a man whose absence enables and structures the band’s own presence.

The wall itself is what Derrida called différance: the structure by which meaning is both produced and postponed. It promises protection while ensuring isolation. Every brick signifies the gap between presence and absence: the difference that allows identity to exist only by deferring completion. Pink finally tears it down, but the question remains: was there ever anything behind it? Or was the wall the only reality all along?

Isn’t this…?

Over the course of ninety minutes, the movie Pink Floyd: The Wall - the band’s name itself obtruding like a brick - is perhaps the ultimate rock opera telling a larger story through song and image. Whether encountered as album, stage show, or film, The Wall shows that haunting lies not in wailings or chain-rattlings but in trauma, alienation, and absence. Among works that confront their own spectrality - The Marble Index by Nico, Closer by Joy Division, The Holy Bible, Nirvana Unplugged - few are as choked with ghosts as The Wall by Pink Floyd.If art is, as Salvador Dalí said, “the persistence of memory”, then it is fundamentally about haunting: an apparitional remnant lingering into the present.

Isn’t this where we came in?

If you liked this, please share!

At a certain point it is incumbent upon us, the consumers of art, to separate ourselves from the artist. While I love Pink Floyd, listen frequently, I care nothing for Waters. Seeing how the man has treated so many, for so long, his opinions, petty struggles, and challenges seem more of his own hand than anything else. It makes reading a well written post a challenge. We don't need no condescension, I have seen the writing on the wall.