Derrida, Commitment, and the Politics of Writing

Derrida, Commitment, and the Politics of Writing

INTRO

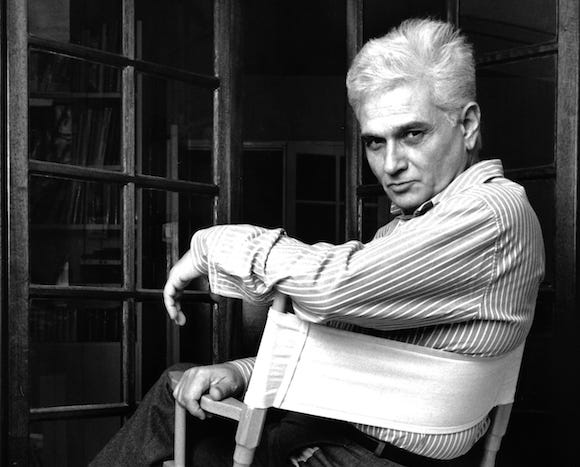

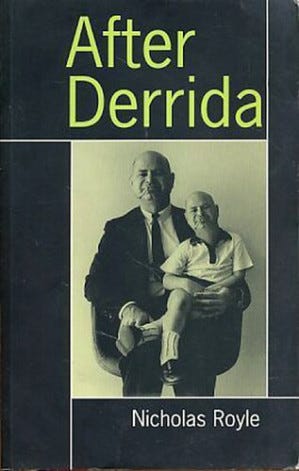

Picture the scene. I’m an undergraduate studying English. During the prescribed Critical Theory module, we have to read Derrida’s essay “Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences”. (My tutor, Dr. Nicholas Royle, is a leading academic expert on Derrida.) The essay says:

Nevertheless, the center also closes off the freeplay it opens up and makes possible. Qua center, it is the point at which the substitution of contents, elements, or terms is no longer possible. At the center, the permutation or the transformation of elements (which may of course be structures enclosed within a structure) is forbidden. At least this permutation has always remained interdicted (I use this word deliberately). Thus it has always been thought that the center, which is by definition unique, constituted that very thing within a structure which governs the structure, while escaping structurality. This is why classical thought concerning structure could say that the center is, paradoxically, within the structure and outside it. The center is at the center of the totality, and yet, since the center does not belong to the totality (is not part of the totality), the totality has its center elsewhere. The center is not the center.

This makes me want to howl. Even if you can parse the sentence, the chop-logic by which he comes to his conclusion that “the center is not the center” is exasperating. The center does not have to be called “the center”, it is not even central: it might be “organising” or “a locus”. It could be in the bloody background. But he has to perform his verbal pyrotechnics to get to his elaborate, non-Aristotelean conclusion where identity is reversed or, as they would prefer to say, undermined. “The center is not the center.” Well done, Jacques, big applause.

Complaints about Derrida’s style and approach have been ongoing for as long as Derrida has been writing. He has the unique (I think) distinction of Oxford academics objecting to his being granted an honorary degree. Yet it’s not just the painful opacity and wilful obfuscation that anger me about Derrida’s writing. To be honest, I find his ideas intriguing. Readers may have noticed several essays of mine that use deconstructive concepts. Identity, speech vs writing, haunting and ghosts, the concept and nature of institutions, and the performativity of literature: these are all useful and intriguing ideas. Derrida is right to point out that texts are not sealed vaults of meaning but unstable, shifting, always haunted by what lies outside them. He is right, too, to see how language is never innocent: every act of naming and defining both reveals and conceals, both empowers and limits. His insistence that philosophy acknowledge its own conditions of language is a genuine and lasting challenge. If you read him with patience, you can see how his work opens up questions of presence, absence, history, and power. These are not trivial concerns. They have shaped literary theory, political philosophy, cultural criticism and even architecture for decades.

But his writing approach seems to me to be fatal. Writing is a commitment: it is saying “This is what I believe”. It is also saying, “This is the world as I see it, and I’ll make you see it too.” Writing is hence always a political act, even when writers are entirely unaware of it, because it makes the reader engage with their world-view. So if you deny that authority, if you say that writing should not deliver clarity (because that would fail to perform the instability of language), you are not shaking the foundations of Western thought, or deconstructing the speech/writing opposition. Nor are you performatively demonstrating the undecidability of writing. You are a bullshitter.

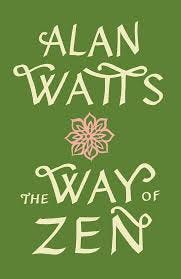

True, some of his followers, such as Christopher Norris, can lay out and clarify his ideas, and some of his works can be explicable. “Structure, Sign and Play”, once you get past the ghastly opening pages, moves to a discussion of Lévi-Strauss that isn’t too hard to follow. Derrida’s ideas are interesting, as I’ve said, especially when summarised and clarified. But they’re not unique. English departments in Western universities act like they’re earth-shattering concepts, but you can find similar dismantlings of thought, concepts, presence and absence in Zen Buddhism, hundreds of years before Derrida.

So if you want the same ideas explicated without intellectual condescension, look to Alan Watts. He is the leading interpreter of Zen Buddhism into Western language and concepts, and does so with a fundamental concern for clarity. He is a teacher who explains. He wants you to understand, because he wants to promote this way of looking at the world. For Derrida, the refusal of meaning is the entire point. But this becomes a pointless semantic carousel, a self-congratulatory verbal exercise. He would call it “play”. But if you’re acting like you’re withholding your own conceptual basis, you’re a coward masquerading as a sage.

In writing, style is not decoration - it is a key part of the content. Language enacts a vision, and thus is a political tool. Let’s look at some examples.

Style as Philosophy

If we consider the French poststructuralists, they have very different genealogies. Derrida comes out of Heidegger. Foucault comes from Nietzsche. And Baudrillard comes from a brilliant stew of Marx, Lefebvre, Bataille, Debord, and McLuhan. (It’s a broad church). This affects not just their ideas but their entire style and creative posture.

Take Derrida. From Heidegger he inherits the phenomenological suspicion of plain speech, and the belief that language must circle, hedge, and dig endlessly into etymology before truth can emerge. Heidegger’s Being and Time opens with “We are ourselves the entities to be analysed” — a sentence that already folds back on itself, denying the reader a clean starting point. Derrida imitates this manoeuvre, as with: “The center is not the center” (“Structure, Sign and Play”) or “différance is the obliterated origin of absence and presence” (Margins of Philosophy, 1972). These are not conclusions but verbal knots that exist to perform undecidability. The style is the philosophy.

Michel Foucault, by contrast, comes from Nietzsche. His concern is not so much the metaphysics of being and presence as the actual operations of power and control. Like Nietzsche, he understands that style is inseparable from thought. Nietzsche’s aphorisms — “He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster” (Beyond Good and Evil), or “We are unknown to ourselves, we men of knowledge” (Genealogy of Morals) — are arguments compressed into lightning. Foucault continues this tradition. In Discipline and Punish, he writes: “Visibility is a trap.” Three words: an entire analysis of surveillance. In The History of Sexuality, he says: “Where there is power, there is resistance.” Each sentence has an edge, draws a line. There is clarity.

The difference is critical. Nietzsche and Foucault commit; Heidegger and Derrida evade. This is not just style but the essence of their philosophy.

The Committed Tradition

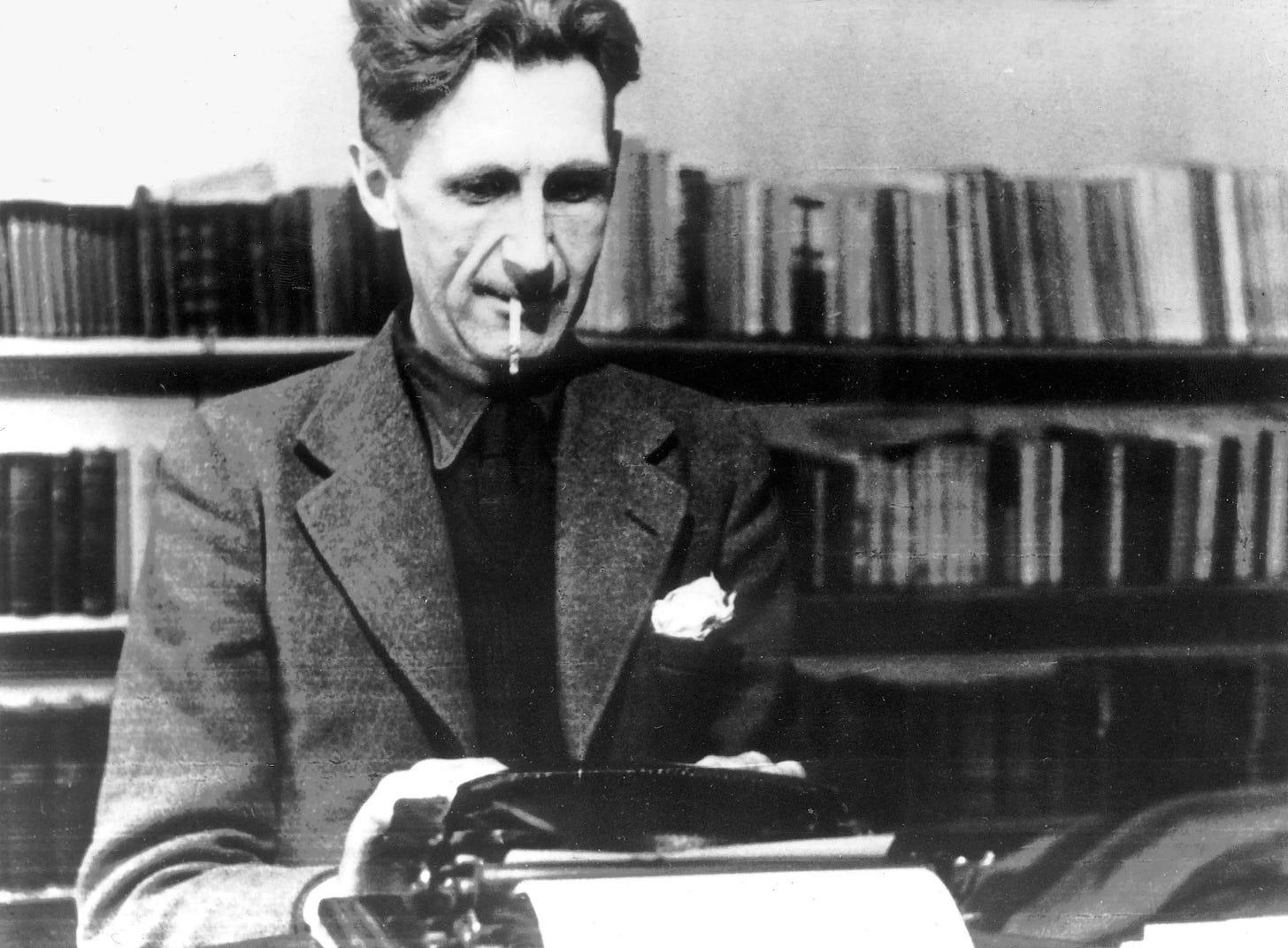

Numerous writers have been explicitly aware of the political challenge of writing and made it part of their artistic approach. The obvious example is Orwell. Writing in a time when propaganda from Soviet communism and German Nazism was undermining the truthfulness not just of media but of the Western episteme, Orwell’s writing was a political act in itself. “Good prose is like a window pane”, he famously said. And if his words occasionally lack a luminous, poetic quality, they make up for it in their unremitting dedication to explication. Orwell tackles an extremely wide range of subjects, from the cup of tea to the English poets of the 1930s to extermination camps, and his plain, muscular writing takes you with him every time. His essay “Politics and the English Language” (1946) is a defence of clarity in writing, but more, it is about good faith in communications. He knew very well how regimes disguised their atrocities and political brutalities: “If thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought. A bad usage can spread by tradition and imitation even among people who should and do know better.” Obfuscation is not just bad faith, or even just political lying. It conveys contempt for humanity.

For creative writers, the need for commitment poses particular challenges. For Scottish writers, who see their own language denigrated as a debased form of English, this creates political inferiority and linguistic subjection. Poets like Tom Leonard and Liz Lochhead therefore started writing in Scots, thereby saying: My language is equal to yours. But it is the writer James Kelman who has taken on this challenge most deeply. In A Disaffection (1989), Kelman removes the distinction between the narrator and the characters. In How Late It Was, How Late (1994), he goes even further, writing the entire book in the voice of Sammy, an underclass Glaswegian man, and eliding all differences between first and third person, between which it slips constantly. For instance: “He studied them; he was wearing an auld pair of trainer shoes for fuck sake where had they come from he had never seen them afore man auld fucking trainer shoes. The laces werenay even tied!” There is no hierarchy of language in Kelman, no superior English narrator explicating the inferior Scots-speaking characters. Sammy’s voice, like Huckleberry Finn’s, centres the book in authenticity. This is a deeply political act - and it was received as such. Kelman’s book was described by Simon Jenkins as the maunderings of “an illiterate savage”. Where Kelman gives humanity, his critics deny it. Which rather proves his point.

Alan Watts has perhaps the hardest task of all, seeking to convey concepts that do not exist in Western thought. Zen Buddhism was dismantling binaries long before Derrida — presence/absence, speech/writing, essence/appearance — but it did so through koans, paradoxes, and silence rather than verbal ostentation. Watts’ genius was to translate this into Western idioms, rendering it in plain English without losing subtlety.

For example, he writes: “We do not ‘come into’ this world; we come out of it, as leaves from a tree.” So he collapses the Western opposition between self and world, inside and outside. Elsewhere, he says: “The aim of Zen is to point directly to the truth, to the heart of life, as distinct from the elaborate abstractions which the mind can spin.” Watts illuminates the same ideas Derrida circles - the instability of categories, the inadequacy of language — but he commits to the reader, taking responsibility for making the concepts comprehensible.

A central insight of Zen and deconstruction is that to force an experience into words is already to lose its essence. “The menu is not the meal,” he observes in The Way of Zen (1956), endorsing the Zen idea that the finger pointing at the moon is not the moon itself. Language divides a seamless reality into fragments, carving up what is continuous into conceptual boxes: self and other, mind and body, cause and effect. But these divisions are arbitrary, human conveniences mistaken for reality. Watts writes, “The mind has the property of chopping up life into bits, as a fisherman cuts a fish into sections.” The world itself does not arrive to us pre-packaged in categories; we impose them, and then mistake the map for the territory. Concepts can only ever be provisional, not the thing itself.

In this way, Watts shows that clarity is not the enemy of depth but the measure of it. He points directly to paradox, and makes you feel it, without quotation marks, hedges, or smokescreens. This is engagement in the best sense, and a commitment to a world view that he knows deeply. Derrida fails, refuses to acknowledge, or hand-waves away, the issue. Let’s see how.

Derrida and the Fanboys

Am I being too harsh on Derrida? How about some examples of Derrida’s prose, and how it compares if simplified. Ready?

Derrida:

Perhaps something has occurred in the history of the concept of structure that could be called an “event,” if this loaded word did not entail a meaning which it is precisely the function of structural—or structurality—thought to reduce or to suspect. But let me use the term “event” anyway, employing it with caution and as if in quotation marks. In this sense, this event will have the exterior form of a rupture and a redoubling.

Plain English:

At a certain point, the idea of “structure” itself shifted. We can call this an event (though “events” are suspect in structuralism): a break with the old view that also repeated parts of it.

Derrida:

The trace is not only the disappearance of origin… it means that the origin did not even disappear, that it was never constituted except reciprocally by a non-origin, the trace, which thus becomes the origin of the origin.

Plain English:

What we call “origins” are never pure beginnings. They are always shaped by what came before - the trace - so that origins themselves are effects, not causes.

Derrida’s style is a choice, plainly, but it is not a wise one. It constantly evades, suggesting that the truth or actual concept is being withheld. I well remember the pained look on Dr Royle’s face whenever a direct question was asked. Meaning to deconstructionists is somehow vulgar, beneath them. Clarity was beside the point, because no text could have a singular, authoritative meaning. To explain therefore was intellectually lower order. So they hid behind endless strategic retreats (they would call this “deferral”): But what does that question mean? And what does meaning mean? And what does “does” mean? And so on. Are you having fun yet?

“Ah,” the Derrida fanboy says. “You’re missing Derrida’s entire point, which is to demonstrate the undecidability of the text, and the removal of authorial intention.” Right-o. But you understood what I’ve written, yeah? So language isn’t that unstable. Of course language is unfixed and moving. We can all think of words which have shifted meaning over time, or which rely on context. But this is no great insight. Making pretty patterns with words in response is not purposeful. It is intellectual onanism.

Unfortunately, Derrida is not just guilty of ghastly writing. He has also launched (or maybe precipitated) the careers of dozens of academics committed to his style. Like Trumpian obsessives, they live out the style of their master but remain in his shadow, in a form of parasocial relationship. Now I’m not saying that prose inspired by Derrida is inherently or always bad. Some writers have done good things with it. Mark Fisher is one. His book Ghosts Of My Life (2014) contains an essay “Home is Where The Haunt is: The Shining’s Hauntology”, explicitly modelled after Derrida’s “Limited Inc”, structuring itself into numbered fragments. But it is witty, penetrating, lucid and comprehensible. For example:

8. The house always wins

What horrors does the big, looming house present? For the women of Horrodrama, it has threatened non-Being, either because the woman will be unable to differentiate herself from the domestic space or because – as in Rebecca (itself an echo of Jane Eyre) – she will be unable to take the place of a spectral-predecessor. Either way, she has no access to the proper name. Jack’s curse, on the other hand, is that he is nothing but the carrier of the patronym, and everything he does always will have been the case.

I’m sorry to differ with you, sir. But you are the caretaker. You’ve always been the caretaker. I should know, sir. I’ve always been here.

Fisher works through Derrida’s ideas but never loses the reader: his fragments build, accumulate, and illuminate. You don’t feel gaslit. You feel enlightened. He proves that even in Derrida’s shadow, one can write in a way that is committed to communication and to its audience. Full marks, top of the class.

Whereas Royle, bless him, was guilty of some of the worst offences against the English language I have ever encountered. Here he is in his book After Derrida (1999), in an essay also styled after “Limited Inc”:

f

To talk about writing in reserve is to engage with the thought of a critical glossolalia, a poetico-telephony or computer network operating multiple channels simultaneously. A sort of hydrapoetics, in effect.

g

Including at least three heads, three tongues, three voices, gathered around the following: (1) how Hartman reads Derrida's Glas (G) in Saving the Text, (2) how this reading is more generally characteristic of the early 'reception' of Derrida's work within English-speaking literary culture; and (3) the possibility of what Hartman calls 'a new concept of reserve'.

h

Writing in reserve: a hydrapoetics or critico-glossolalia. As simple as abc.

This is nonsense. Let’s take the first segment. “Writing in reserve” — writing held back, not yet in use - but then it is immediately said to be operating in multiple channels simultaneously. Which is it, reserve or operation? It can’t be both. Then: “critical glossolalia” — literally, critical babble. But glossolalia means meaningless tongues, religious gibberish. How can gibberish be critical? (Unless this is a wry comment on critical theory as a whole. But I doubt it). “Poetico-telephony” — poetry by telephone? A telephone has one line. It cannot be “multiple channels simultaneously.” And then “hydrapoetics”? A hydra is a monster with many heads biting at once, each incoherent with the others. If poetics implies an art of voice, a euphony, then hydrapoetics is the negation of poetics — dissonance, incoherence, heads talking over each other without sense.

This is why it is worthless. Each metaphor, when examined, collapses into contradiction. Royle’s writing has no commitment to sense, the reader or anything except literary posturing.

The Fog of Jazz

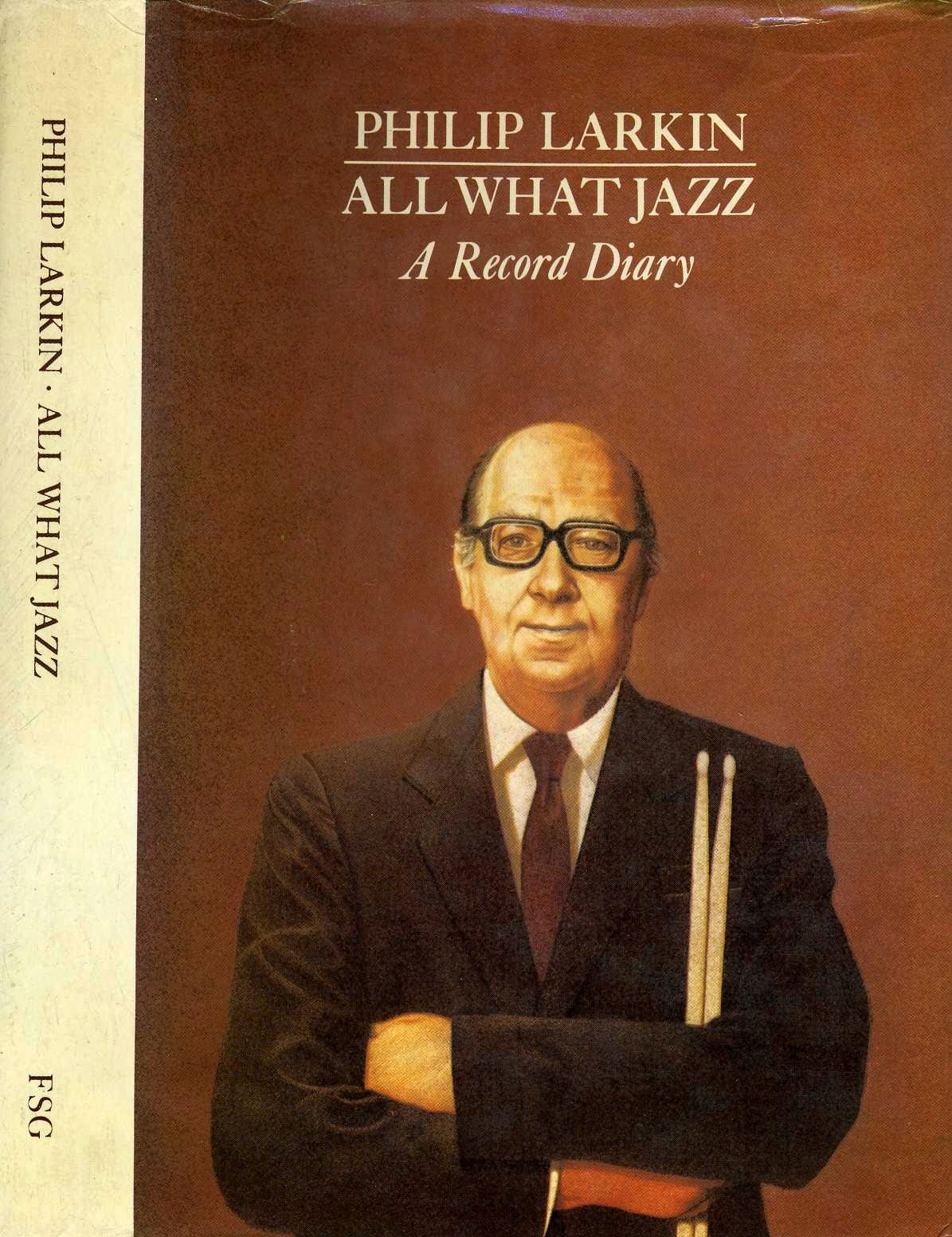

It is worth remembering that the fetishisation of obscurity has recurred across the arts. Philip Larkin, in his essay “The Pleasure Principle” (Required Writing, 1982), savaged modern jazz for exactly this tendency. For him, the move from Armstrong and Ellington to Parker and Coltrane marked a collapse of artistic communication. Jazz stopped speaking plainly; it became self-regarding, technical, a private language for initiates. “You either got it, or you didn’t.” And if you didn’t get, the fault was yours - not the performer’s.

This is precisely the Derridean trick: to make incomprehension feel like a personal failure. Where Armstrong wanted to connect, late-period Coltrane seemed to demand surrender. While Coltrane’s cover of “My Favourite Things” was adventurous and exploratory but still melodic, late albums Ascension (1966) and Meditations (1967) were clanging, atonal, deliberately barbarous. (I can sort of enjoy their intensity for brief periods, but I'm always drawn back to tunes with melody). The idea was the same: difficulty as proof of seriousness and depth. In jazz it was “the new thing”, linked to Black Power and civil rights. Jazzmen were artists, and they would play whatever the hell they liked. The audience didn’t come into it.

Larkin, of course, was dismissed as reactionary. Even his biographer Andrew Motion says his point is racist, because Larkin is effectively demanding that black artists entertain white audiences. But Larkin’s point is colour blind, simply about art and audience: if music is not used to communicate, if musicians deliberately cut themselves off from their audience, they are not being profound: it is solipsism with a beat. That insight links Larkin’s jazz writing with Orwell’s defence of clarity, and with Kelman’s commitment to voice, and with Watts’s Zen paradoxes. It is all one tradition: the insistence that writing, music, or philosophy is only serious when it binds itself to lucidity.

Deconstructing Institutions

But if Derrida is so painful to read, why is he such a hero of the Western academy? Larkin probably got it right when he railed against the complexities of modernist art:

The terms and the arguments vary with circumstances, but basically the message is: Don’t trust your eyes, or ears, or understanding. They’ll tell you this is ridiculous, or ugly, or meaningless. Don’t believe them. You’ve got to work at this: after all, you don’t expect to understand anything as important as art straight off, do you? I mean, this is pretty complex stuff: if you want to know how complex, I’m giving a course of ninety-six lectures at the local college, starting next week, and you’d be more than welcome.

The desire for difficulty occurs when audiences are separated from the everyday tastes and concerns of the average consumer. Progressive rock developed following the expansion of the universities in the 1960s: now there was a market for expansive, intricate and occasionally pretentious music. You wouldn’t get a wonderfully esoteric album like Tales From Topographic Oceans (1973) by Yes (with lyrics like “Dawn of a light lying between the silence and sold sources / Chased amid fusions of wonder

In moments hardly seen forgotten / Coloured in pastures of chance, dancing leaves cast spells of challenge”) in any other context. Same with jazz, and art, and literature. Deconstruction might see itself as inimical to institutionalisation, but its rising influence from the 1970s onwards is also a reflection of expanded university departments and the need to move beyond merely teaching literature.

So during my English degree, during the unit on poetry, entire techniques such as meter, assonance, consonance and caesura went unmentioned. This seems to me now to be an incredible dereliction of educational responsibility. What mattered was not equipping students with tools to analyse poems, but deconstructionist ideas about presence, self-identity, and internal difference. No matter whether we knew the difference between iambic pentameter and trochaic tetrameter. If the old skills of scansion or rhetoric were too easily mastered, they lost their institutional value. They weren’t research, which is how departments were assessed and from which money flowed. Poststructuralist obscurity therefore guaranteed the lecturer’s employment.

This is the dirty secret of theory. Its difficulty was essentially a survival strategy. Derrida may have deconstructed “the center,” but he created one of the most powerful centers of all - an academic industry that flourished because it was impenetrable to outsiders. “You either got it, or you didn’t.” And in doing so, academic responsibility to literature and students was weakened. Their commitment was plainly elsewhere.

After The End

When first studying Derrida, I assumed the problem was mine. If I just read him more carefully, eventually I would “get it.” That was the tacit promise of every course: persevere and the fog will clear. But it never did. This is the trick of Derrida. He makes you feel that your incomprehension is your failure, not his refusal. For years I believed if I were just a little cleverer, more diligent, and more devoted, I’d find the clarity. Now I know: there is no clarity. It is a pointless linguistic game. He is not a charlatan, but his stratagems are counterproductive, even infuriating.

Writing, as Stephen King says, is telepathy: the transmission of ideas, arguments and visions from the writer to the reader. But Derrida and his imitators insist on garbling the signal. Yet the real difficulty, as Orwell knew, is precision. Obscurity is not philosophy, nor its rethinking - it is the abdication of seriousness. To write is to commit – to paper, to the reader, and to the idea. Without that, there is only fog; but with it, there is light, fire, and the power to change the world. The power of writing comes always from its commitment.

If you like what you read, please share and subscribe!